A story of a crossing of Iceland, unsupported, by foot and inflatable packraft. You can read the books of my other journeys here.

A note before I begin:

I deliberately never talk about maps and routes on my website. It’s not meant to be a recipe book. But I get so many questions about this Iceland trip that here are a few facts for anyone wanting to do something similar:

- We walked south from Akureyri, over the highlands to the Hofsjökull glacier, then down the Þjórsá river. We walked the Landmannlaugur trail then paddled the Markarfljót to the sea.

- The rivers are quite dangerous in parts. We portaged round parts that were beyond our skill levels. Glacier travel is also potentially dangerous.

- We used Alpacka Llama packrafts and carried all our food and kit for a month.

- We bought our maps from Dick Phillips, Whitehall House, Nenthead, Alston, Cumbria CA9 3PS (01434) 381440

I hope these help if you are planning a trip. Iceland is one of the greatest places I have ever been. It would be virtually impossible to plan a trip here that wasn’t brilliant!

I was ready.

I had trained hard and planned carefully. I needed this. The last few months had been claustrophobic back home.I was straining at the leash, more eager than ever to get out ‘there’, out into the wild places. To be free for a while; to simplify; to test myself. I was ready.

But, like men down the generations, the siren song of the three age-old distractions snared us first: wine, women and… whale meat.

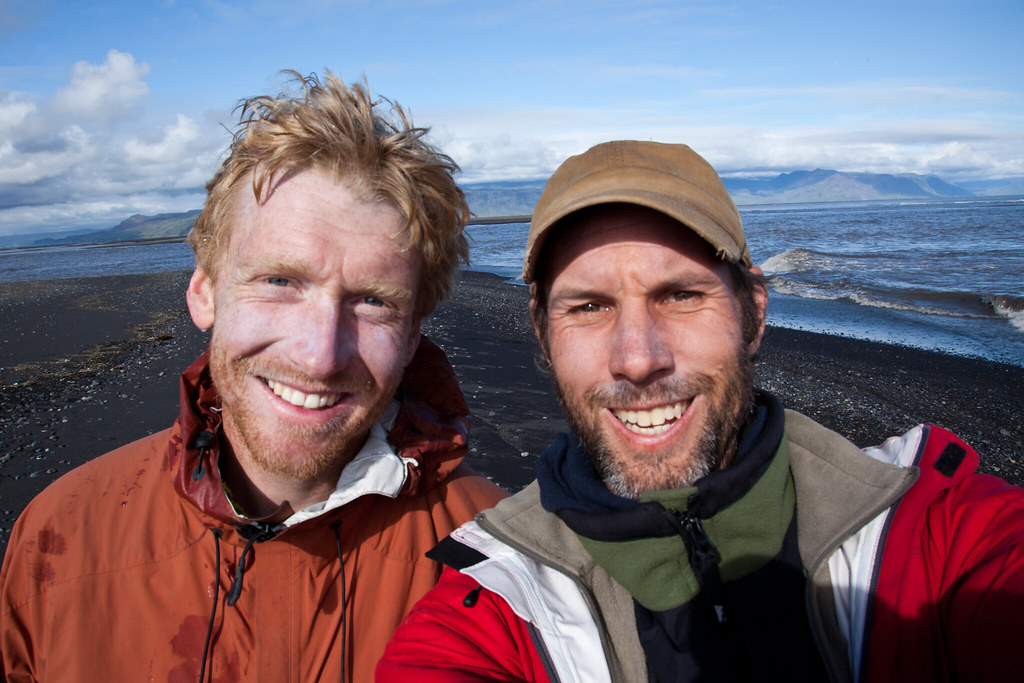

A family had kindly invited Chris (friend and expedition partner) and me to stay before we began our journey. After a barbecue we experienced Iceland’s extraordinary stamina for all-night partying. We drank and danced right through the sunlit northern night into the morning and consequently felt far too rough to begin the trek.

So we delayed for a day, delayed the shock of heaving 40kg packs onto our backs, delayed pointing our noses south and hiking away from the cold, empty, wind-whipped beach that marked our start point.

When we did begin we hiked just a few hard miles and then we stopped. We were tired, our heads hurt, and our packs were alarmingly heavy and painful. We pitched the tent in the rain, and we slept.

Then in the morning we began in earnest. The plan was simple: we were trekking inland from Iceland’s north coast up into the central highlands. We would cross the Hofsjokull ice cap to gain access to the headwaters of Iceland’s longest river. There we would inflate the packrafts we were carrying and attempt to paddle down two separate rivers, eventually reaching the southern coast of Iceland, the ocean, and the the end of our expedition.

We were carrying everything we needed. There would be no villages or resupplies on our route. We carried food for 25 days. We had camping equipment, and ropes and crampons for the glacier crossing. There was a fair weight of camera equipment, batteries and solar panel chargers. And we also were carrying all the gear you need for paddling glacial whitewater rivers. The weight of the packs crushed our knees and spine and gouged our shoulders and hips. We feared that we had bitten off more than we could chew.

Despite that we began anyway, hiking up a fjord through a narrow fertile river valley, whistling 80’s riffs half-remembered from the other night.

In misguided high spirits I leapt into a river for an evening swim, and then spent the rest of the night shivering cold in our wet tent. We were rained on every day for the first two weeks as we left behind the green fields, Icelandic ponies and noisy streams of the low lands.

We climbed steeply to the head of the river valley. Up there were the highlands. Icelanders speak with trepidation, even today, about “the highlands”. Notorious in days gone by as a refuge for outlaws and highwaymen, there is no sign of human life in the highlands, and little sign of any life at all. There are no streams or birds or trees.

Today there may no longer be the brigands of days gone by, but the magnificent desolation of the highlands still holds an unmistakable aura. The endless rain seeped through our clothes. Our laden packs sapped strength and spirit. And the highlands felt a foreboding obstacle, as they have for hundreds of unchanging years.

Were we ready? We were about to find out.

And the rain fell, and the winds blew and slammed against the tent. Days of rain turned into weeks. The world was monochrome. Icy rain and flurries of snow challenged our lightweight clothing. We wore every stitch of clothing we owned and still we were cold. The only colour came when we escaped from the world, into our little red tent at day’s end.

The days were wet. Our kit was wet. Our cameras were wet. We trudged across the black stones of Iceland’s highlands, each step identical to the last, each day the same as the one before. The same but wetter. Wetter and hungrier.

Carrying food for 25 days means that you must learn to be hungry. We simply could not carry enough food to replenish all the calories burned by a hard day of exercise with a heavy pack. And the more food you have in your pack, the more calories you burn carrying them. So hunger is inevitable.

For breakfast we shared a small pan of porridge and raisins. Then we broke up the long day with two chocolate bars, a handful of nuts, and a morale-boosting inch of salami. Come day’s end we were ravenous for our boil-in-the-bag meal with an added spoonful of calorie-rich butter. Each day our dinner grew more delicious, yet it also seemed smaller than ever. We were consuming about 2000 calories a day, yet burning thousands more. It’s a pretty simple weight-loss programme, if not a particularly fun one!

The highlands are notorious in Iceland. For being so lifeless that NASA astronauts trained there for their moon landings. For being flat and stony and boring and repetitive and featureless. And for occasional glacial rivers that are too swift and cold to ford. We knew all this in advance. Yet still we found it tough. Navigating on a compass bearing through thick, wet fog in an unyielding icy gale was made more difficult by the ferrous volcanic rock all around us. The needle swang wildly and we steered an approximate course. We were unlikely to miss our target though: we were looking for the third largest ice cap in Iceland.

The endless days of grey sapped morale. Chris, being a professional photographer, fretted about the lack of photographic opportunities. I worried that our slowing progress and troubles caused by too-heavy packs may come to jeopardise the whole trip. I worried silently that we may have bitten off more than we could chew.

A gale was thrashing our tent. It had just switched through 90 degrees, and was now threatening to blow the tent over completely. Chris was sending a text message home from his phone.

“There’s no predictive text for YIPPEE,” he shouted above the wind.

“What on earth do you have to say ‘YIPPEE’ about?!” I wondered.

But, in my weird way, I was loving this harsh lunar landscape. The river crossings were cold and hurt like hell. But when I put my boots on again afterwards my feet felt so clean and tingled pleasingly. If you looked carefully you could find tiny pink flowers that clung to life on the godforsaken sterile gravel. And nobody on Earth knew where we were. There were no signs of people, no signs of human life (though having perfect reception on the mobile phone rather dented this sense of isolation!).

I had nothing to do each day but navigate and walk. Nothing to worry about but how long remained until my next Mars bar. Nothing to think about except whatever I wanted to think or dream about. I snatched bearings from brief glimpses of mountain peaks through the clouds. And I urged myself to keep walking, not to put down the pack and sit and rest. That was all I needed to do. Just keep walking. The miles and days passed. My frustrations from home faded away as I peered into the gloom, deciding that the rain on my face felt ‘fresh’ not ‘cold’ and that though my feet and shoulders hurt and my belly growled continually, there was nowhere else I would rather be.

Chris’s ankle was hurting him and he whacked a rock with his trekking pole in frustration. His pole snapped. I turned to hide my giggles as he swore loudly at the world.

At last a grubby tongue of ice began to loom through the mist ahead of us, rising high out of an endless black sand plain. The Hosfjokull glacier. And it stopped raining too. We camped at the foot of the ice cap. I laid out my stuff to dry and drank in the gentle midnight sunshine. I was happy to have finished the wasteland of the highlands. A new phase of the expedition awaited. The next day we would fix crampons and climb up onto the glacier in search of our river.

Can you think of a better beginning to a day than to emerge from a tent (after a hellish night of storms) to a world of clear sunshine and still silence? It was particularly welcome on the morning we climbed up onto the Hofsjokull glacier. I am no expert on glacier travelling, but I’mm always eager to have a go at things. The difficulty with this mentality is steering the right line between stifling caution and rash recklessness. This morning’s rare clear skies helped tip the balance.

So I packed the tent quickly, eager to get up onto the ice while the weather was good. I knew that bad weather was bound to roll over us soon: this was Iceland, after all. But if we could get up there, get going, and feel that we were within our capabilities before the rain and sleet and mist returned then we would have more motivation to keep going. For I was anxious that we did not talk ourselves out of trying to cross the glacier before we even began it. I desperately wanted to head up and over it to the headwaters of the Þjórsá River. We could have skirted the ice and joined the river further down. But I wanted to do the job properly, despite my lack of glacial expertise. I really wanted to begin our river from its true headwaters, not halfway down at some easy and convenient spot. My motivation came, as ever, not so much from wanting the experience itself as from not wanting to not have the experience, the challenge, the lesson…

We hiked up the steep, rocky morraine to the ice. Rocks and gravel slipped and crunched beneath our feet. We slid one step backwards for each two or three climbed. It was tiring, but we made it to the cold ice at last. Strapping on crampons and digging our rope out from the bottom of the backpack I felt a blossoming of excitement in my gut about this next stage of the expedition. I crunched across the ice to peer over the rim of the first crevasse, and felt a squeeze of primordial fear at the black, fathomless maw gaping up at me.

The ice cap, Iceland’s third largest, was grey and grubby. Ash from Eyjafjallajökull’s eruption had smeared across the whole landscape, robbing us of the stunning blue colours you often associate with ice.

[ice on the Hofsjokull ice cap]

But the murky grey ice fitted well with Iceland’s murky grey sky, heavy rain, and falling temperatures. But where rivulets of meltwater ran across the glacier’s surface small channels of bright blue had been carved out.

We were high above the plains of central Iceland and we looked out over hundreds of silent, empty miles flecked with occasional gleams of sunshine shards slicing through the cloud. Meshes of grey-brown glacial streams flowed out from beneath the ice in all directions. We studied our map to match it to the rivers, gleaning information to bring our map to life. We knew very little about what awaited us when we reached our river. Would it be deep enough to paddle? Would it be too fast or would it be flat and boring?

Chris and I continued across the silent expanse of cold, grubby ice, our crampons crunching with reassuring friction beneath our feet. This was such a different experience, and a different challenge, to climbing up from the green, moist lowlands or slogging across the bleak highlands. And the next phase, paddling Iceland’s longest glacial river, would be different yet again. The variety of this expedition was its greatest attraction.

Crossing to the snout of the Þjórsájökull glacier we saw the maze of small streams that would combine somewhere in the murky distance to form “our” river below us. We thought that the hardest part was now behind us. This is rarely a wise thought to think.

Down off the glacier we removed our crampons beside a narrow but fierce stream that was gushing from an ice cave at the foot of the glacier. It was impossible to know for certain if this was “our” river. Maps were of little use in that ever-shifting, homogenous landscape. The water was grey with silt and freezing cold. The rain continued to fall. But at least this racing water was heading towards the same coast that we were. We had crossed Iceland’s watershed so it was downhill all the way from here.

Now we followed the course of this stream on foot until it became large enough for us to paddle. But we found ourselves in a hellish landscape. Beneath our feet were rocks and gravel. But the going was more like quicksand. Everywhere was saturated. We sank knee-deep into rocky gloop at every stride. We crossed stream after stream, searching for solid ground, silently begging the river to grow, and loudly swearing at the cold, exhausting slop we were wading through.

We still did not for sure whether this mesh of little streams was going to grow into a proper river heading the way we wanted to head. Like pioneers trying to read the land we climbed a ridge to peer ahead. There were so many river channels we could follow now. What we had to do was to choose one, and then live with our decision.

In the end we took refuge back up on the glacier, finding it easier to traverse along that than to follow the hellish meanderings of the rocky swamp valley. At long last though the river appeared to be widening, gathering volume from countless other tiny streams gushing off the glacier. We pitched camp beside the river. All of our clothes were drenched with mud. We cooked a disgusting dinner with grey muddy water. It was especially unenjoyable as I had bought all of our dehydrated food at a discount because it was years out of date. Normally this was not a problem but just occasionally we would have a meal that tasted disgusting. Disgusting but we did not have any spare food. So I swallowed it down as fast as I could and decided that this expedition sucked. As I climbed into my sleeping bag, I consoled myself that at least the worst must now be behind us. Tomorrow we would be paddling. Surely that would be fun?

When paddling a river it is wise to know what lies in wait. However it is not always possible to scout ahead. We were about to begin paddling Iceland’s longest river, the Þjórsá. Information on the river’s condition was scarce. Few, if any people, had paddled up here, and certainly not in a packraft. We had a map, the best I could find anywhere. It was from the 1930s. We knew of at least three large waterfalls but there could be more. We knew that the river sprawled its way across massive wetlands in a complicated web of shallow channels and dead ends (see aerial photo, above). So we knew some of what lay ahead. But the detail we were going to have to discover for ourselves.

We were both excited as we inflated our packrafts on the river bank. We had followed the river from the Hofsjokull glacier where it began life as a narrow, ugly little stream. Now it was wide enough to paddle. It was time for the next phase of the expedition.

You get wet paddling whitewater in a packraft. Very wet. But we were travelling too light to carry drysuits. So we donned an extra wooly jumper beneath our GoLite waterproofs. We also wore neoprene gloves and booties and a hat. We placed our backpacks inside large drybags and lashed them to the bow of the raft. The bright red and blue boats were a jaunty splash of colour on the grey glacial water.

With whoops of relief that today we did not have to hike with 40kg packs on our backs we took to the water. We cheered with excitement as the boats slipped out into the current and suddenly, effortlessly, we were moving faster than at any other time on the expedition. This was more like it!

Within two minutes our cheers were stifled. We had begun on a broad, flat stretch of river on a broad, flat plain. It could not have been more innocuous. So how the hell did we suddenly find ourselves plunging into a canyon and Grade 3 whitewater?! Big waves of ugly, grey meltwater reared in front of us. Things happen fast on a river. We hurtled into, over, through the waves and then smashed off a drop-off. It was thrilling and I am sure I was shouting very loudly. It was very wet and very cold. It was fantastic fun. And it hit me hard how bloody far we were from the nearest human should anything go wrong.

As soon as we were able we tucked into an eddy to catch our breath and ask each other what the hell had just hit us. Chris’ eyes were like soup plates. “Munchers!” he said, over and over. ‘Munchers’ were his name for the waves we had somehow made it through. For the rest of the trip we spoke of munchers a lot, partly hoping not to encounter any more, partly looking forward to the prospect.

We emptied our swamped boats and pondered the situation. We had been paddling for just minutes. But already we were soaked to the skin and had scared ourselves silly. I was kicking myself that I had not had time to take any photos or video of the rapids. Neither of us intended to repeat the experience for the camera.

The prospect of giving up so soon was bleak. Besides, neither of us was keen to carry the cursed packs any further than was necessary. So we paddled on. As Murphy’s Law dictates nothing else interesting happened for the rest of the day. We paddled narrow channels, having to get out occasionally to drag the boats when the water was too shallow. But usually we just swooshed on through, for packrafts float happily in only a foot of water.

The river ran parallel to the glacier. We paddled along in the lee of a huge, hulking wall of ice. To our right the flat stone plain ran empty all the way to the horizon of two stark conical mountains and another ice cap. Clouds rolled across the sky, shifting the patterns of light across the land. Two swans, the first birds we had seen in days, flew past, white against the grey cloud. It was a desolate, yet beautiful landscape, and a wonderful privilege to be floating through it.

But by day’s end we were freezing cold. We draped our wet clothes over the tent to dry in the forlorn hope that it would not rain in the night. I boiled water for our food and, as we waited for the food to rehydrate, we lay in our sleeping bags with the bags of food between our feet like hot water bottles. By now we were becoming extremely hungry and finished each meal seemingly as hungry as we began it.

What had prompted us to stop for the night was that we were lost. Getting lost on a river takes some doing when all that is required is to paddle downstream. But the river’s flow had slowed and the river widened so that it now resembled a lake more than a river. We could not see where any outflow to the lake may be. So we stopped for to explore on foot.

What we found was that since our 1937 map was made our river had been dammed! That was a surprise, and an annoying one at that. For there was no significant water flowing out of the man-made lake. So we were forced to pack up the boats and start walking once again. We walked downstream for a whole day before sufficient other glacial streams combined together to make the river deep enough to paddle once more.

I remember one campsite in particular. I remember it not merely because the sun came out and I stood and basked for ages. Not merely because the moment the rain and wind stopped plagues of flies rose from the earth to cloud our eyes and nose and mouth. I remember it because it was a beautiful, silent, empty evening with a view unchanged for millennia. And because at that moment almost everyone else in the world was glued to their televisions watching the World Cup final. The wide river slid by. I hope that every four years for the rest of my life I will think back and remember that evening.

As an avid football fan it had been a bit of a gamble to plan an expedition for the second half of the World Cup. But England’s pathetic performance meant that they were already out of the tournament before I even began. Football fans measure their lives by seasons rather than years. I remember where I was in 1991-92. I remember where I was in the summers of ’86, ’90, ’94, ’98, ’02, and 2006. And I will remember Iceland 2010 for as long as everybody else will remember Frank Lampard’s disallowed goal.

The next phase of the river was perfect. The glacier framed spectacular views. We tackled bigger and bigger rapids and our confidence grew as we learned to read the river better. We wove slowly through a wetland region home to millions of migrating geese. And we were kept alert by knowing that, sooner or later, round this corner or some corner soon, we were going to encounter a bloody big waterfall that would kill us if we didn’t get ashore fast enough. And all of this we had to ourselves.

A ferocious hailstorm lashed over us and I took shelter on the shore underneath my boat until it passed as suddenly as it arrived. Sheepish sunlight seeped through the black storm clouds onto a landscape suddenly white like winter. On one occasion we had run out of water to drink. The land was barren, the river too silty to drink. So we were amazed to find a tiny island in the middle of the river that was bubbling with a fresh water spring. The small surprises and good fortunes often become the most lasting memories.

Being provoked to think was one of my incentives for choosing this journey rather than just doing another version of some trip I have already done before. In an ideal expedition your brain and your principles should be as challenged as your body. The packrafting aspect of this expedition was giving me lots to think about:

- balancing risk-taking with pragmatic caution

- is fear of the unknown a valid fear?

- is it acceptable to be not 100% in control of a situation even if you are x% confident of being in control of what to do if things go wrong?

- where is the fine line between bravery and recklessness?

Thankfully one of our regular scouting forays revealed the series of waterfalls to us in good time. I was not even slightly tempted to try to paddle them and was more than happy to portage our stuff round. We felt so fortunate to have waterfalls as spectacular as these completely to ourselves. Iceland has so many incredible waterfalls that these were virtually nameless and unknown.

The waterfalls had gouged out a steep green canyon so we ended up camping high above the river on a steep hillside overlooking a thundering waterfall.

That night I felt a sense of deep contentment such as I have not really felt in the last couple of years. I lay on springy green moss outside the tent and looked down at the rainbows of mist drifting from the waterfall. The trip was turning out to be all I could have hoped for. Beautiful, deserted, challenging, daunting, and with very amusing company. I’mm a lucky man. One day like this a year’d see me right.

Packrafts bring variety and freedom to your travels. They are not ideal if you would rather hike the whole journey. They are not ideal if you would like to paddle the whole journey. They are ideal if you’re looking for adventure, and whatever comes your way.

We chose not to paddle the Þjórsá all the way to the sea. Instead we packed up the boats and set off on foot once more to go and have a look at the volcano that had been causing such chaos across Europe all year. Like everyone else in Europe, we couldn’t say its name. But we wanted to have a look. From there we would take to another river to work our way down to the sea.

We decided to incorporate Iceland’s most famous long-distance hike into this stage of the journey. I have been writing a few travel pieces for the Sunday Times recently. They are not interested one iota in my macho tales of derring-do. Rather they want stories that may encourage other people to go out and try the same thing. The 4-day Laugavegur trek seemed ideal for this. It was rumoured to be remote, difficult-but-do-able, and very, very beautiful. It would also lead us to the foot of the famous volcano. We hiked for a couple of days from the river to Landmannalaugur, the start of the hike, and then started the hike. Still following?

The trek turned out to be everything that I had hoped, and more. It should be as famous as the Inca Trail; it is certainly as rugged and beautiful, but without the trail of backpackers’ pink toilet paper along the way.

The Laugavegur is one of the great hikes of the world yet is little known outside Iceland. It is a four-day trek that begins in a lava field, crosses rainbow mountains, passes bubbling pools and glacial ice, crosses a black ash desert, and finishes in green woodland at the foot of Eyjafjallajökull, the now-famous volcano.

My trek began, as all great journeys should, wallowing in a hot spring beneath the midnight sun. The pool lay at the foot of a labyrinth of jagged lava that long ago oozed slowly down the flanks of the volcano above me. Relaxed and clean I wound through the lava towards clouds of stinking sulphurous steam gushing from cracks in the hot earth. Getting into my stride now, I climbed steadily up to a pass striped with an extraordinary range of colours.

Over the crest was a hole in the rocks, a spring boiling like a cauldron and gushing down the hillside. Tearing myself away from bubbling springs and bright blue pools I crossed a dark plain shimmering with obsidian, a black volcanic glass. The view was magnificent with a glacier to the north, and mountains all around.

Post-porridge, the second day began crossing small valleys and snow bridges in warm sunshine. Below lay a vista straight out of a Lord of the Rings film. Volcano cones stretched across a green plain slashed through with shining streams. On the southern horizon was grey and grubby Eyjafjallajökull, a cloud still streaming slowly from its crater.

Day three was completely different again. It began with one of the route’s three memorable, cold river crossings. Ahead, whirlwinds of dust and ash swirled across the spartan black landscape. The magnificent desolation of rocks and sand resembled a lunar landscape. I could understand why NASA trained the Apollo astronauts here.

The Markarfljót river races through an impressive canyon. From the rim of the canyon you can look down to the rapids far below you, or southwards down the valley towards the oasis of Þórsmörk (pronounced “Thorsmorkâ€), the end of the trek. After four days of wilderness Þórsmörk’s birch trees and flowers smell so sweet after the sterile mountains and plains. They makes for one final surprising twist on this most enchanting of treks, one that rates as high as any I have done in the world, and a real highlight of Iceland.

(I have also put together this audio slideshow of photographs and a recording I made along the trail.)

Oh, and as for the name of “the famous volcano”: like many place names in Iceland, it became less of a tongue-twister as I began to learn the meaning of its component parts from my maps: Eyja = “island”, fjalla = “mountain”, jökull = “glacier”. The mountain with a glacier that can be seen from the islands off the country’s south coast… Eyafjallajökull. Simple!

We stood at the source of the Markarfljót River.

It was time to follow this river south, south to the sea.

The sea, the end of the river’s journey, would also be the end of ours.

Rivers’ sources are always beguiling. All the unknown land that lies ahead, the building of momentum, and all the other obvious metaphorical parallels with journeys in general. But the beginning of this river was even more intriguing than usual. I looked into a bucket-sized hole between two boulders. Boiling water was churning noisily. It gushed out of the hole and I was engulfed in damp clouds of steam. This tantalising glimpse into the fiery volcanic underworld was the source of the river that would lead us to the sea, that would frighten me very badly, highlight the conflict between hubris and humility, and force me to address the question of “what really is the purpose of this expedition?”

Chris and I followed the steaming stream down a small ravine alongside a grubby swathe of last year’s ice. Plumes of sulphurous steam flowed from the earth. There were small pools of dazzling blue and hot mud puddles that farted comically.

The stream plunged down a large waterfall and headed off on a meandering route, recruiting the force of many other tiny streams as it went. We headed due south and intercepted the river again as it thundered, big and bustling by now, through the Markarfljót canyon.

The canyon is impressive. We look over the rim. The murky glacial water seems silent as it is 170 metres below us. But it is racing and frantic down there. The canyon walls are sheer. Vertical. Jagged and multi-coloured with bands of red, green, brown and grey. The canyon is gloomy. It’s too steep for the afternoon sun to penetrate down there. The bottom is littered with gigantic boulders.

White birds sweep through the air far below us. They add to the sense of separation I feel up here from the river down there. The river looks angry. Can we paddle it? I imagine how tiny we would feel down there in our little boats. Is the water too rough for our packrafts? Are there any sudden waterfalls along the way? If so, what can we do about it? Is there any way out of this canyon once we commit to it? We have many questions but few answers.

We spent a whole day scouting the canyon, hiking along it and peering down to the river below. The simplest option would be to not attempt to paddle the canyon. To trek past it and then enter the river once it settles down a bit. But if we were taking the easy option then we would not be paddling any of Iceland: we would just have walked across the whole country. So I wanted to paddle the canyon. Why? Because it would be exciting, challenging, thrilling, difficult, and therefore rewarding. But it is harder to justify attempting something dangerous when there is a safe alternative. I knew that I would regret it if I didn’t make an attempt to paddle the canyon. I also knew that I would really regret it if we died!

We were both quiet, sitting above the canyon wrapped in our own thoughts. We talked occasionally, evaluating the pros and cons. I said that I wanted to give the canyon a go. Chris wanted to know how I had reached my decision. It was hard to articulate and impossible to quantify, but I felt strongly that I had reached a measured decision rather than a reckless impulse. The essence of it was:

“there is an x% chance of something going wrong. If that happens then I am y% confident of being able to deal with it. Which leaves only a z% chance of something really bad happening. And ‘z’ is sufficiently small to be worth risking against the reward of success.”

I think that this is the sort of process most risk-takers process before making a difficult decision. But normal people probably just articulate their decision by shouting,

“f*ck it – let’s do it!”

So we did it. Or we tried to. Unfortunately there was no way to get down into the canyon to launch. The only place we could climb down to river level was in an offshoot canyon. The tributary river in this gorge rushed from the glacier behind us to join the Markarfljót. But the river was noisy, churning and powerful. It was much worse than the main river that we had been agonising over. But we had no alternative. And it was only a short stretch until it joined the main river. And we really wanted to paddle the beautiful canyon. And we had spent so long scouting. And we had climbed all the way down into the canyon now. And it looked bloody exciting. And is it not a good thing to do a thing that scares you sometimes? We decided to launch. I would go first. Chris would film me. Then he would follow along and I would wait for him to catch up at the entrance to the main canyon.

I pushed out into the current. I was nervous. The waves in the river ahead collided noisily with the sheer canyon wall as they swept round a bend. I was excited and I was alert. The flow was so fast. I paddled hard to channel the adrenalin that was coursing through me. I grinned and whooped as I hurtled past Chris. By then I was completely committed to whatever would be. Nothing, absolutely nothing in my life mattered now except these moments. Nihilism, reductionism, and my little blue boat. This was the biggest water I had ever paddled alone. Then Wham. The waves thumped me and swamped across the boat. I was scared. I felt very calm and focussed. The water was cold. But that’s alright because I like the way it hurts. I ticked off each wave as I guided the packraft through them. “Good. Well done. One more. Here we go. Concentrate.” I lifted my paddle above my head, our signal that all was OK. The packraft was doing brilliantly. It felt stable and manoeuvrable. The largest waves bent the boat in half, but it recovered well each time. Heavy, cold water was all around and all over me. My rucksac and all my gear were strapped tightly onto the bow. On top of that my GoPro camera was facing forward catching footage for our film. [Except that I later realised I had put a dead battery into the camera so actually failed to record any of it. Still a source of anguish!]

I felt on the edge. I was treading a fine line here. I felt alive. I felt that I wanted to stay alive. Keep going. Keep living.

But then ahead of me in the river I saw a bus-sized boulder, right in the middle of the current. In an instant I watched the whole flow of the river crashing against it and funneling down each side of it. There was no chance for me to get to the side of it. Smash. I crashed straight into the boulder and slid up, up, slowly but fast, vertical it seemed, and only then did gravity act and dumped me over and backwards and upside down into the water.

Then chaos.

I am underwater, in churning, silty, freezing water. I am surprised that I feel very calm and very alert. I think clearly, “this is now a serious situation”. The only person in the world who can help me is upstream. He can only reach me by paddling the way I have come. He cannot come the way I have come without capsizing as I have done. I am under an Icelandic river, clinging to the paddle in my left hand and hoping that I will be spat up to the surface soon. I am on my own. Truly on my own.

I surfaced and gulped a breath. I grabbed my raft, shoving an arm through a loop of rope and hanging on tight. Under I went again, swirled round and round. Then up. Then down. It was time to get out of here. I remember being impressed at the river’s speed. I managed to half swim, half push myself off rocks until I was near to the river bank. I hurled myself at an eddy and got hold of a rock. I chucked my snapped paddle onto the bank and braced myself against the weight of the raft and pack that were still in the full flow of the river. With all my weight and strength and will I couldn’t drag them in. I was starting to lose my grip on the boat. Should I save myself and lose the boat and all my gear? No. I jumped back into the whitewater with the raft and hurtled downstream again until I managed to heave the raft and pack out of the river onto the bank. Wowee. Safe. Wow.

I paused for just a moment to realise that I was safe and how lucky I had been. And then I was sprinting up the rocky river bank as fast as I could, slopping bedraggled and coughing wildly, clutching my safety throw rope. Waving my arms and blowing my whistle and hoping like crazy I could catch Chris’ attention above the noise of the river before he reached this stretch. I blew that damned whistle so hard and I waved my arms and thankfully caught his attention in time.

We no longer had any dilemmas about paddling the canyon. We packed up our rafts and climbed back out of the steep canyon to hike round it.

Despite having a very close shave, and probably acting in a way that experienced kayakers might find naive, stupid, and dangerous, I still believe that we were right to attempt that stretch of water. But I also believe that we made the right decision when we gave up.

Further downstream the river opened up in the lee of the volcano Eyafjallajökull. The ground was covered in fine grey ash from the spring eruptions. The volcano’s glacier was black with ash. Steam billowed from the volcano. And whenever the wind rose the sky would cloud over with ash, the sun reduced to a feeble orb through the thick, dark atmosphere.

We climbed a peak to gain a better view of the river ahead of us. The Markarfljót flows across a broad plain in a mesh of streams, each one shifting constantly. When glacial floods scour the land the whole course of the river changes. So there is no way to map a river like this. You just have to paddle by instinct, trying to steer towards the deeper channels. Make a mistake and you pay the tedious price of getting grounded again and again and having to drag the raft through the shallows until you reach deep water once again.

At times Chris and I lost sight of each other in this stage. The river was so wide and it was very hard to steer to ensure that you both went down the same narrow channel. The black and ugly flanks of Eyafjallajökull’s glacier rose on one side of us. On the other bank, several hundred metres away, we began to see occasional small, red-roofed farms in green pastures. White waterfalls cascaded down the flanks of bright green fells. We were returning to the world, returning to civilisation. The sky in front of us was open, wide, and enormous. A sea sky. We were almost there.

It was a frustrating final day, trying to find clear passage through the web of shallow streams. Pick your path and take your chance. We paddled under the bridge of Iceland’s ring road, the one paved road that runs right round the country. A few cars passed along the road. It seemed so busy. I was being returned with regret to the real world, decompressing, saying goodbye to the wild and the wild times, and also looking forward to the real world. Looking forward, above all, to food! We were both very hungry by now. Over the last week I had grown dizzy and weak. It was time for burgers and beer.

But first of all it was time to paddle to the sea. To the end. We floated across a featureless flat world. Seabirds swooped and dive-bombed us, aggressively defending their nests. The sun, for once, shone warmly. To an audience of lounging seals and circling seabirds, we paddled out into the brown waves of the Atlantic Ocean and the end of the expedition.

Crossing Iceland was one of the best journeys I have ever done. I travelled with a tough, talented and amusing friend [Thanks, Chris, for putting up with me!]. Iceland is a stunning country just 3 hours’ flight from London. It was a fairly cheap expedition as well (especially thanks to the half price, out of date food!). And the plan was simple in concept but tough in execution. It was exactly how an expedition should be.

Some practical advice for an expedition such as this:

- EXPEDITION KIT LIST FOR ICELAND

- ACROSS ICELAND BY PACKRAFT – A GEAR REVIEW

- KIT REVIEW FOR GEOGRAPHICAL MAGAZINE

If you’ve enjoyed reading about this expedition why not get one email per month from me with the best bits from the blog and any latest news?

Nice article with good information, especially for people thinking about doing a similar trip across Iceland. Seems like you complained a lot though, instead of just cracking on with it. Not enough food, always wet, windy conditions… that’s what you want when going to Iceland isn’t it? Also, I’m all for a bit of preparation but if you over do it it takes the fun out of it, in my opinion.

Haha! Apologies for the excess of complaining – it was actually one of the most fun trips I have ever done.

Sounds awesome. I was looking up Iceland treks and saw this. How many miles would you say you walked and do you know how many you averaged a day? I’m just asking to see what would be in my scope.

Prob about 20 miles a day.

Very beautiful

But they do not allow me.To see the place

They do not give visa

I am a Iranian

What an expedition!! Great inspiration and advice in many aspects for expeditions.

Hey Alastair, thanks for sharing your great adventure.

When you say 40 kg packs, I guess you mean between both of you in total, isn’t it?

I was carrying about 22kg hiking in Iceland last 2 summers, (including food and water) the first year I got very bad cramps on my neck, the second one was slightly better, but I need to solve the problem for next time.

Not sure if my backpack is not good enough to be attached to my body properly, or I’m just not good setting my gear into the backpack.

I’ve got your book “Grand Adventures” yesterday, I can’t stop reading. Thanks!!!

40kg each, sadly!

Outstanding! I´ve just started doing packraft-tours and think about a tour in Iceland. Thanks for this article as inspiration!

Whaling is illegal in every English speaking country, yet you contribute to this disgusting, barbarous practice as soon as you step out of your country.

I would liken you to a dirty old man, visiting a brothel in Thai Land.

Hi Phil,

It’s a tricky thing to arrive as a guest in a stranger’s house, on your first day in a foreign land, to then be served a meal you were not expecting, and to then refuse that meal. I did not ask for whale, I did not choose it, it was already cooked.

Yes, perhaps I should have shown more moral courage.

But I think your comparison is a little harsh!

Best Wishes

Hi Alastair,

What an amazing trip. A group of us are planning on running across Iceland this summer. Could you tell me what maps you used please?

Cadi

Please see the note at the top of my blog about maps.

Good luck with your run – I LOVE Iceland!

Hi Alastair,

nice photography! Some shots look surreal with a moon-like scenery.

I still need to visit Iceland, but it seems a no-brainer for any nature-enthusiast.

Thanks for sharing your adventures!

Best,

Barbara

Truly delightful accounts of your dedication to unique and extreme adventuring. I always enjoy both your account as well as that great photography. We drove the Ring Road a few years back as the first trip on our bucket list to start traveling unrestrained by the idea that we had to wait for retirement. It was just as exhilarating each day fir us discovering the immense beauty of the geology and natural inspiration of Iceland. Thanks fir taking the time to share your process along with your adventures. As I read about your hunger I appreciated having a small Toyota, snacks from Costco (Keflavik), and the immense pleasure of a great meal of lamb and fish at the end of each day in delightful spots like Vik or Borgesfjordur Eystri. I most enjoy the wide range adventures – 10 hours exploring stunning geography, warm simple bed, good food, repeat. I am looking forward to a 2022 EU exploration for a book I am writing that I reheated the roots of nature mythology. We’ll start with a week exploring Dublin. Greg will fly back to work while I take the ferry to Wales for 3 weeks and train about to various Druid and cultural spots, then Paris for a few days with a friend to gear up for a 3-week roadtrip through art and nature spots through S.France to Barcelona for a week then home to the paradise where I live on the Point Reyes National Seashore. Come visit with your family sometime for the leisure version of adventure-light (heavy on a comfy bed and good food). Kind regards.

We did the same trail this year and it was unbelievable beautiful! Thank you so much for this recommendation!