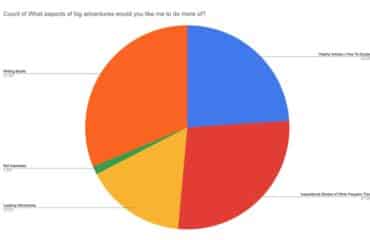

A very interesting article on the need for risk in life, the stifling of risk-taking in today’s society, and the power of the great outdoors to inspire, humble and educate us all.

By taking risk, we take life by the scruff of the neck and shake it. Without it, we are simply passengers…

[Read the whole article by John Horscrofthere]

Not long after I moved to Sheffield, I discovered a perfect bike ride that took me from my front door onto the moors of the Peak District. Arriving at the highest point of the ride, I stopped to savour the view. To my confusion, I found myself choked with emotion as I looked down on the city. I slowly turned to take in the subtle contours of the Peak District around me, and was overcome by the moment. That ride is now a reference point, as deeply etched on my memory as some of my fondest climbing moments. If what passes for wilderness in our crowded isle can elicit such a response, how important is it to the health of the nation? Equally, how much might outdoor pursuits contribute to the general well being of our society?

The nineteenth century American philosopher Henry David Thoreau advocated the great outdoors as a source of succour to the masses, a refreshment to the soul, a kind of free psychotherapy. One of his most famous aphorisms is “in wilderness lies the preservation of the world.” Is this profundity or truism, penetrating insight or trite? To answer, we must look at the man.

Thoreau was no idle dreamer, he was a pragmatist believing that civilisation and wilderness could, in fact should, co-exist. A pioneering educationalist who believed in introducing children to the wonders of nature, he advocated a simple life in natural surroundings, was an exponent of hiking for pleasure, and was convinced that wilderness should be preserved as public land. He felt that only through experiencing nature would man come to love and cherish it. In short, he was one of us.

It’s arguable that Thoreau’s thinking led inexorably to the national parks we enjoy today. One of the founding principles of Britain’s first national park, the Peak District, was that it should be open to the public. There was a recognition that those who toiled all week in the factories of the north, industrial Britain’s engine room, should have a safety valve. Access to the beauty of the Peak District should not be confined to the moneyed few, but should be open to all. There are cynics who would say that the demise of heavy industry has lessened the need for such a haven for the working classes, but are they really suggesting that today’s stressed out wage-slave doesn’t need the balm of a walk in the fresh air?

The fact is that Britain’s open spaces are as important now as they’ve ever been. As Thoreau said ‘Men have become tools of their tools’. Thus time away from the tyranny of the computer, television and Playstation is time to reflect, time to understand the importance of simple pleasures and re-awaken the imagination.

Far too many people in our society have suffered a childhood devoid of adventure, untouched by Britain’s open spaces, and have maintained that indifference into adulthood. Unfortunately, this is not universally understood either by those who would benefit most nor those who could legislate to encourage it. While the Government lectures about fitness and health, it subsidises the National Opera more than it does the Peak District National Park Authority.

What kind of skewed priorities hold sway when the rights of the opera lover take precedence over the nature lover? Were the government to pay more than lip service to the value of the outdoor life, the payback would be far beyond the outlay from the public purse.

The great outdoors is a source of unlimited free exercise for mind and body, and the positive effect on both the physical and mental health of an individual is self-evident. And for most of this website’s readers, there is a further and more complex dimension to this discussion, and the clue is in the name ‘planetFear’.

Risk is an essential part of the equation for many of those who spend time in the wild and participate in adventure sports. The quote with which I began is sometimes subtly altered to “In wildness lies the preservation of the world.” Even misquoted, Thoreau’s dictum is profound. The innate wildness of childhood, the determination to take risks, to test oneself, and the desire to cross unchartered terrain, is something that shouldn’t whither with age. Rather, it should become a fundamental part of adult life. Those of us who indulge in risky activities know instinctively that the experience of risk is good for us. We don’t need academics or educationalists to spell it out.

The rush you get from having completed a testing adventure race or surviving a particularly fraught climbing experience can last for days. It can be resurrected in a flash when the need arises, when the monotony of the working week threatens to overwhelm you. Colin Mortlock, educationalist and theoriser on the subject of risk, equates action with reflection and says in his book Beyond Adventure, an Inner Journey: “Quality action and quality reflection on that action are of fundamental and equal importance.”

Our adventures are much more than simple thrill seeking, they are problem solving, brain stretching, heart pumping experiences. They add context to existence, tone to muscle and cultivate self awareness. They can immeasurably enhance our friendships and relationships. By taking risk, we take life by the scruff of the neck and shake it. Without it, we are simply passengers.

Pioneering American psychologist William James suggested that “the problem of man is to find a moral substitute for war”. Some find that substitute in work and business, some in Grand Theft Auto, and still more in the vicarious pleasures of the telly. Which poses the question. If these are the only examples we set our children, is it any wonder they become prey to addiction, nihilism, and violence?

In a society prone to media-led hysteria, exposing children to real risk is becoming problematic. The multi-million pound health and safety industry is predicated on the false notion that not only risk in the workplace, but risk in general, can be controlled and legislated against.

This notion is fundamentally wrong. Sir Digby Jones, the Government’s Skills Envoy, has recently said that an obsessive “safety first” approach to life is creating a generation of children who are ill-prepared for a world that requires daily risk-taking to achieve success.

Outdoor education has provided an escape route for many a tearaway, although too often these days it is reduced to a couple of hours of top-roping or easy paddling. The challenge is for us to use our open spaces to their full potential, and to provide kids with the opportunity to experience real risk on their own terms. For this to happen, we must deal with the inevitability of accidents. We turn a blind eye to chilling road casualties, yet treat every death in an adventure situation as a cause for national mourning.

The equation is simple enough. If we wrap our kids in cotton wool, they will make their mistakes at the wheel of a car, with a knife in a dispute among their peers, or with a syringe. If we expose them to real adventures in the great outdoors, they will learn from the experience and carry that lesson for the rest of their lives.

Government has yet to understand that if you attempt to eliminate risk in outdoor education, you also destroy a crucial – perhaps central – part of its inherent value. Colin Mortlock, founder of Outward Bound and one of Britain’s leading outdoor educationalists, has been trying to get successive governments to comprehend this for several decades, with limited success.

I recently rode the Glentress trail centre in the Scottish Borders, one of the finest mountain biking runs in Britain. As I toiled up the innumerable switch-backs to get to the top of the red route, I found myself surrounded by a group of taciturn teenagers led by a guide. When we stopped for a rest, they stopped with us and we attempted to engage them in conversation. The thickness of their accents and the fluency of their profanities encouraged the belief that they were probably from one of Glasgow’s less blessed areas. Eventually, we followed them to the top of Spooky Wood, one of the most celebrated downhills in the country. We looked on in wonderment as the guide briefed them, amazed that he was going to take them down such a testing run. He suggested we went first, and we set off gladly, assuming that carnage would follow. Arriving at the bottom with whoops of glee they congregated round us excitedly, wreathed in smiles, garrulous and plied us with questions.

“What’s this place called? I’mm coming back!”

The transformation was miraculous. Exposure to risk and the sheer exhilaration of the run had instantaneously transformed stroppy teenagers into lively and inquisitive young people. I am absolutely convinced that the experience of riding Spooky Wood was a life changing moment for some of these youths, whose only ‘real’ adventures to date had most probably been running from the police.

The combination of wilderness and risk is a fine example of the concept of hybrid vigour:- the result is greater than the sum of the two parts. Society underestimates the importance of open spaces and adventure at its peril. To characterise risk-taking as perverse or selfish is to ignore the importance of testing oneslf, of using this mortal frame as more than a receptacle for junk food and junk culture. Let Thoreau have the last word. “This world is but a canvas to our imagination.”

Comments