Ben Saunders is a pioneering polar explorer and a record-breaking long-distance skier, covering more than 6,000km (3,730 miles) on foot in the polar regions since 2001.

Ben’s accomplishments include leading the longest human-powered polar journey in history, a round-trip from the coast of Antarctica to the South Pole and back again that retraced Captain Scott’s ill-fated Terra Nova expedition for the first time. He is the third person in history to ski solo to the North Pole and holds the record for the longest solo Arctic journey by a Briton.

Ben is a very good friend of mine and I was delighted to chat to him for Grand Adventures.

Alastair: Which of your expeditions are you most proud of?

Ben: Wow – straight in with the hard questions! I’mm going to have to say it’s the last one, the Scott Expedition. Even now I can’t put it into words. It was so much harder than I ever thought it was going to be and it just took so much to get it off the ground.

There were so many years and years and years where it seemed like everyone was doubting, I was doubting whether this was actually going to happen [it took Ben ten years to get the trip off the ground]. Just to get down there and start it felt like a triumphant achievement really. So it was an extraordinary experience.

Alastair: There’s a massive amount of iceberg beneath the surface of an expedition in terms of getting it off the ground. Do you enjoy that aspect of it or in a dream world would you just turn up at the start line and go?

Ben: I’mve always dreamed of having some sort of secret benefactor who gives me huge chunks of cash and then I could just have a stealth expedition with no sponsors, no social media, plain clothing, no logos, no flags, and just go and do it for the hell of it really.

I’md love that. But sadly I don’t have enough money and the niche that I’mve chosen is ridiculously expensive. For me to have done it, I’mve always had to find sponsors.

I’mve always dreamt of having some sort of secret benefactor who gives me huge chunks of cash and then I could just have a stealth expedition with no sponsors, no social media, plain clothing, no logos, no flags, and just go and do it for the hell of it really.

Alastair: I was looking through today your sadly demised blog. Back in the days before I knew you and I only knew you through your blog, I used to think you were amazing…

Ben: Well, that’s why now I just have a one-page man of mystery page; I just hoped that people might continue to mistakenly think that…

Alastair: Ha! Anyway, I read a sentence where you said, “Here’s to those who are still quietly chipping away at the edges of impossibility.” That really fits with what you’ve just done with the Scott trip.

Ben: That was a good line! I’mm proud of that line. Maybe I nicked that from someone, I don’t know. It is important to me though to be doing something that isn’t a contrived stunt. It was genuinely inching things forward in the field that I care about. So I’mm glad that we did that.

Alastair: That aspect of it is what I loved about the years I was involved in the South Pole trip [I was Ben’s partner on the trip for five years of planning but sadly had to pull out. It’s one of the great sadnesses of my life.] – the wondering about whether or not it was possible.

Ben: Yeah!

Alastair: And I felt I was willing to, in my case, give up five years of my life for that dream. You gave more than ten years. And that’s why it’s great to see you finally get there at the end. It made the whole project seem validated and that I wasn’t wasting my time tilting at windmills.

Ben: It’s funny. I had dinner last year just after I got back with Tony Haile. Tony and I sat down more than ten years ago and hatched the original plan for this trip. He’s gone on a totally different path. He’s now in New York, he’s a very successful CEO of a big tech company there. He’s married and he’s got a very sensible life.

We had this 12-year reunion over dinner and he asked at one point, was it worth it, the 10 years. And I wasn’t really sure how to answer that, but I think for both of us there was a bit of the grass being greener on the other side.

I think I envied the fact that he had this very sensible life and very high-flying career in New York and I think that he probably envied that I’md done the trip that we’d dreamt of doing as slightly naive 23-24 year olds.

Was it worth it? I’mm not really sure how to answer that.

Alastair: Do you mind that so few people get what you do, that people lump your South Pole trip in with that girl who just drove a tractor to the South Pole? Does that bother you?

Ben: It used to. I’mm still sort of chewing over this now, but I think for a long time I imagined that once I did this trip, everything would somehow change. It would miraculously transform my life. And, of course, when we stepped ashore, Tarka and I, at the edge of Ross Island [the end of the trip] and you take the step from the ice of the Ross Ice Shelf to the rubble shore of Ross Island, and nothing changed. Nothing happened. There wasn’t a magic wand that just ended the trip and cast a spell.

And in some ways, it was a giant anticlimax. In other ways… I’mve been doing this stuff for 13 years and I thought I knew how hard it was going to be, and it was just way beyond anything I could imagine.

And that’s speaking as someone who theoretically is an expert in this stuff. So for me to expect the layman to be able to look at what Tarka and I did and somehow objectively evaluate it is totally unrealistic. That’s why Tarka was such a great teammate because he has zero ego. He just doesn’t care about external validation. He’s got no interest in any sort of public recognition or fame. He’s just totally unfazed. He doesn’t even own a mobile phone. He was just the perfect teammate. He’s got no Twitter, no Facebook, nothing.

We went to Greenland, Tarka and I, last summer ’13, as a little dress rehearsal for three weeks. And I was really at the height of the sponsorship, with tons of money going in and out and we had huge contracts with lawyers, everything was nuts. I had inadvertently become the CEO of this bizarre business that was turning over tens of thousands of pounds a month. And we had lawyers, and accountants, and PR people, and we had an intern, eight people in the office, a huge payroll to meet. It was just bonkers. I was thinking, “What on earth is going on?”

And to suddenly be transported to Greenland for three weeks with Tarka and to be with someone who is driven purely by this genuine love of the wilderness: it was perfect timing because it reminded me why I started down this path in the first place. And if I was doing it for public recognition or something then I was barking up the wrong tree, because I was doing something that was so specialised in such a weird niche that no one’s really going to appreciate it.

Alastair: No honour and recognition in case of success…

Ben: No, none really. It’s been funny. I think one of the biggest lessons is that earlier on, I think there was a lot of ego involved and I wanted to make a name for myself and prove something, I don’t know, do something that I’md be proud of. And I think the biggest lesson of this last expedition has been the importance of being able to de-couple achievements or praise or criticism or any of that stuff from self-acceptance and self-worth.

Alastair: Is that also a combination of growing up and not having a chip on your shoulder, all those things that young people have?

Ben: Yeah, exactly. I guess nearly four months of nothing in Antarctica was a great chance to think about, “Why on earth am I doing this stuff?” I think earlier on I wanted to be Ranulph Fiennes. I wanted to be famous, I guess, and I’mve realized that actually getting to that point takes a massive concerted effort. You have to be ramming your stuff down other people’s throats very hard for the whole time to start getting asked for autographs in the street. I’mm quite ambivalent around celebrity at the moment, how much I want to elbow my way into other peoples’ lives and minds.

Alastair: Yeah, of course. Tell me about it. More and more I think of my job description as being “showing off about myself on the internet.”

I was reading an interview you did about eight years ago and you said, “I’mm really hoping that I’mll be happy after the South Pole, that I can draw a line under it and say that’s enough of the big stuff.” So are you now done with the big stuff?

Ben: I feel I’mve scratched the itch for now. It’s funny. Tarka, I think, feels that there’s still some unfinished business. The fact that we had to get a resupply [the expedition attempted to complete the 1800 mile journey with all of their own supplies, but they had to call in for a small resupply of food], I think he still feels that if we did a few things slightly differently, then that journey could be done without support of any kind. We were so close. Tarka and I spent the whole of the return journey debating, “What if we’d done this differently? What if we’d done that differently?”

Theoretically if we had one extra day of food at the start, we wouldn’t have needed that resupply and it would have saved us £100,000. It would have been a flawless, perfect expedition – the thing I’mve been dreaming of for years and years and years.

But of course Tarka didn’t have to raise the money. So I think if I could just turn up and do it again, it might interest me but the idea of having to raise that money from scratch puts me off. And anyway, no one would get it, “You’ve done it. Why should we pay for you to do it again?”

Alastair: But if someone gave you all of the money and flew you to the start line, do you think you would have the mojo to go through it all again?

Ben: Interesting. I think at some point in the future. But not right now.

Alastair: I want to talk a bit about failed trips, the couple of North Pole attempts you did. One when your ski binding broke and the other when the weather scuppered things. How much of an impact has those failures had on you? The reason I’mm asking you this is because I think one of the things that stops people doing stuff is they worry about failing too much.

Ben: Looking back, weirdly, I’mm extraordinarily proud of those trips, even though the last North Pole attempt didn’t even start! We didn’t even get a weather window. We raised the money, did the training, flew out there, and the weather was so crap that we couldn’t even start. We waited for three weeks and then you’re too late in the season…

How do I say this? I was trying to do something that mattered to me and that I felt was genuinely chipping away at the boundaries of what was considered possible. It would have been a lot easier to do a normal style North Pole trip with a longer time window and more food and to be one of the list of people that have done that. But I wanted to do something that was in some sense pioneering.

So I’mm kind of proud I kept bashing away at that, and each time, I managed to pick myself up and go back and try again. And of course with each of those attempts and with the months and years of planning and training, I was learning stuff that actually meant that we got to a position where the Scott expedition was a viable undertaking. Looking back at each of those trips, even the biggest failures, even the ones that didn’t start, they were all crucial stepping stones to getting to where I wanted to be.

Ironically, I don’t think I’mve ever had a completely successful expedition. On every journey I’mve done, I failed to achieve everything I’mve set out to. In that process though, we’ve done some cool things. I’mve genuinely raised the bar in this weird little niche. We broke the record for the world’s longest ever polar journey on foot. The longest ever man-hauling journey in polar history. And I’mve done that through failing over and over again.

It would have been a lot easier to do a normal style North Pole trip and to be one of the list of people that have done that.

Alastair: I think that’s a massively important lesson to learn. All the things that you have achieved are what really counts. And you only achieve those by not being scared to fail and therefore setting the bar higher than you would do otherwise.

Ben: Absolutely, yeah. Looking back, it sounds clichéd, but the only failure would have been not to try in the first place. That, to me, is the only acceptable definition of failure, just to not actually try.

Alastair: Jon Muir said exactly the same thing to me this week. He’s a proper legend.

Ben: Amazing, amazing. And he just surfaced on Twitter, hilariously.

Alastair: I feel both happy and sad that he’s on Twitter.

Ben: It’s like John Ridgway or someone popping up on Twitter.

Alastair: Mentioning Jon Muir is a good chance for me to talk a bit about the career side of your approach to things. I think the single biggest thing I’mve learned from knowing you for all these years is just the professionalism that you manage with every little detail of what you do.

Comparing you to Jon Muir then – he is obviously professional in the expeditions he dow, but you’re much more at the businessman-type end of things. Do you think that’s because the trips you do need a lot of cash? Or is it what you like?

Ben: It’s because they’re so expensive. I’mve had to figure it all out from a starting point of zero. Before my first expedition I’md run a couple of marathons for charity but that was it, as far as fundraising went. I didn’t know anything about fundraising or sponsorship or marketing. I had to figure it all out pretty quickly. In fact, my first expedition landed me in so much debt that it would have taken me years in a normal job to pay it off.

So I thought, “I’mve got to figure out how to raise more money. Otherwise I’mm going to go bankrupt.” I had to figure out how to be more professional about the business-y side of things.

You asked earlier if I enjoyed the fundraising. I never enjoyed it but I just saw it an integral part of the challenge. If it was as simple as just signing up somewhere and you get flown out to the Arctic, then there would be thousands of people out there.

So I saw it as part of sorting the wheat from the chaff and the wannabes from the people who were actually seriously committed. So many people contact me asking for advice for expeditions. The dreams that actually come into fruition is a tiny, tiny percentage. So, to me, the fund raising and sponsorship nd paying the rent and putting food on the table for years is all part of the challenge really and I guess even though it’s been nightmarishly hard, part of me relishes that. I quite like being up against it, I guess.

I saw it as part of sorting the wheat from the chaff and the wannabes from the people who were actually seriously committed.

Alastair: The other thing you do really well (which I never do and always intend to do) is not trying to do everything yourself. You’re very good at surrounding yourself with good people, paying people money to do their stuff – Andy Ward, Andy McKenzie, Tem, all these people. I think that’s a really important thing that you’re good at and I don’t do at all.

Ben: Yeah, in some ways, I learned tons about running a business, which I never expected to, through these expeditions. I learnt an awful lot about how hard it is managing a team. Looking back, at times I fear I did a terrible job of being a manager. I think there’s a real difference between leadership and management. I think in some ways I did okay as a leader. I definitely had the vision. I knew what I wanted to happen. I knew that I needed a lot of help to do it. But I’md really underestimated the challenge of keeping this giant team going and looking after them, and making sure all of their needs as human beings were being met.

I didn’t think that’s what I’md signed up for in this kind of career choice. I didn’t think HR was going to be part of it, but it was actually one of the toughest challenges.

Alastair: Do you ever consider sometimes just saving up a few grand and going off to do something bonkers somewhere or do you think you’re all set on this polar specialism stuff?

Ben: I don’t know. It’s weird. Right now, I don’t really have massive ambitions for another long trip. Maybe that’s a temporary thing. Maybe that’s just because I’mm still processing Antarctica and recovering from that journey. But I think in some ways, I’mm content with what we achieved. I don’t feel I’mve got an awful left to prove when it comes to chafing and dragging heavy stuff around, enduring a long time in a tent without washing. But some of my favorite trips have been just a car and a one-man tent and driving off to Wales or Scotland or just doing a microadventure.

Alastair: Why, back in the day, did you set off on the path of being a specialist polar guy rather than the more generalized adventurer? Because you could have still been a very professional but generalist adventurer.

Ben: Yeah, that’s a very good question. I started out with fairly generalist ambitions. Years ago, when I worked for John Ridgway, I did a lot of sailing, a lot of kayaking. I had planned initially to go away from that and to go and get a Yachtmaster Certificate to be able to skipper yachts. And we did one trip with John out around the Outer Hebrides and I got really sea sick, and it was really quite frightening. It was very stormy at night, big high seas, nearly capsizing a couple of times. It just totally put me off. It was a completely petrifying experience. So I went off sailing!

I used to like climbing a bit as a teenager. I loved reading about mountaineers and climbing expeditions, and the really cool sort of cutting edge Alpine stuff that was going on when I was growing up. So for a while, that was an ambition as well.

And then there was something about polar expeditions that just caught my imagination, and I read a lot of books around the same time. They were things like Ranulph Fiennes’ Mind Over Matter about his crossing the Antarctica with Mike Stroud, Footsteps of Scott by Roger Mear and Robert Swan.

It’s weird. There were a few stories and a few images that, for some reason, just stuck in my mind and I thought, “Wow, that looks like a proper adventure.” My first polar expedition was with Pen Hadow in 2001 and I thought back then it would be a one-off. I never imagined it’d become a career. I wanted to experience the Polar Regions myself. He seemed like a good guy to be able to take me out there and show me the ropes.

Looking back, certainly there’s something about the scale of the places, the remoteness of the places. The intensity of the conditions and therefore the kind of experiences and emotions that you go through. They’re enormous highs and lows, and I think there must be something almost addictive about that kind of intensity, because as humans, we seem to seek out experiences of intensity.

We go to big rock concerts, or we go on roller coasters, or we like having fast cars, we like spicy curries or getting drunk or taking a drug, or whatever it is. We seek out experiences and stuff that’s intense. To me, hanging out in a cold tent in Antarctica, for some reason, that’s the thing that does it for me. I think I very ill-advisedly said this in a TED talk once. I think I compared it with having a crack habit.

Alastair: It would be a lot cheaper.

Ben: Yeah, and it’ll probably have the same effect on my relationships. Yeah, it’s probably being much like being a drug addict in that from the outside it looks hellish and you can’t really explain what’s so compelling and appealing about it unless you’ve tried it.

I remember talking to Rosie Stancer a few years ago. She is one of a very small, very tough gang of ladies trying to become the first woman to ski solo to the North Pole, because that hasn’t been done yet. She said the hardest thing about solo expeditions – big, long ones – is the knowledge that no one else can ever or will ever know what it was like.

You can try and explain, but no one else has shared that experience with you. In some ways, that’s very precious and very special, but in other ways, it’s frustrating when you try to explain the experience to others.

Alastair: I think that from my cycling around the world. One of the hardest things now, many years on is that fact. I think one of the reasons I found it harder to settle down to any semblance of normality is the lack of empathy from anyone.

Ben: Yes, absolutely.

Alastair: Do you prefer solo trips or those with other people?

Ben: It’s so hard to choose. I love the simplicity of solo trips, and the fact that you can live to your own routine, go as fast or as slow as you want, pick your nose/fart/snore/etc in the tent. But sharing the experience of the big trips can be magical, and in my experience the right team mates can also pull you out of mental and physical troughs. I loved our Greenland trip with Martin – there was no real objective other than skiing for a bit, turning round and skiing back, and seeing how we all got on, but it was great fun, and a real joy sharing such a special place with two (often piss-taking) mates’¦

“There’s no secret to it. You just get used to rejection and keep bashing away. If you’re told no once, that doesn’t mean they’ll say no the next time you try. “

Alastair: The email I get asked most, and I am entirely the wrong person to get it, is about sponsorship. What are your top tips to get sponsorship?

Ben: I wrote to Ranulph Fiennes when I was about 17 asking him the same thing and he very kindly wrote back. He said something like, “There’s no secret to it. You just get used to rejection and keep bashing away.” Yeah, now maybe 20 years on, that was about it really. It sums it up. There’s no magic to it. There’s no secret.

In some ways, it’s getting easier than ever because anyone can be a producer, publisher of content now. It’s content, and stories, and imagery, and exciting engaging stuff that companies want. That’s what they’re buying. That’s the magic they’re after. It is easier than ever now to record your story and to share your story. In some ways, that makes things easier. In other ways, that makes things harder because anyone can create a website for free and call themselves an adventurer or explorer. It’s a more crowded space than ever.

I think persistence is probably the most important thing. I think you’ve got to look relatively professional although I’mm amazed at the sums of money that I raised in my early to mid-20s for some really audacious goals. I first contacted Land Rover in 2000 and I first signed a contract with Land Rover in 2008. So it took me eight years to get that dream partnership.

So keep bashing away. If you’re told no once, that doesn’t mean they’ll say no the next time you try. Their goals change, their marketing strategies change, the marking people change.

For smaller expeditions, not the million dollar ones, look at local businesses. My first ever big sponsor was a company in Kent who made plasterboard. They didn’t do anything to do with the outdoors, but it was just a local business and I got some local publicity for them and they put in some cash.

Don’t automatically go after Red Bull or the North Face or Oakley, but think of brands that are trying to get into that space. Be a bit more creative. Do some research and try to find the up-and-coming challenger brands.

The other thing is to not underestimate the value of what you can do for a company internally. One of my biggest ever sponsors, Serco, back in 2004, don’t sell anything to the public. They had absolutely no need whatsoever to raise awareness of their brand. For them, it was purely internal. They wanted to follow my expedition. They wanted to feel they had some sense of ownership in it and it was something that united their international workforce of tens of thousands of people.

I remember the buzz words were “a unifying focus”. I’mll give you that for free.

Alastair: Thank you.

Ben: Everyone will now put that in their proposals!

Alastair: Thank you, Ben. One thing that’s always annoyed you, one of the many I should say, is seeing pictures in the paper of some guy who’s about to go on a polar expedition, dragging a tyre around a park. What are your top tips then for training properly for an arduous, physical expedition?

Ben: I feel guilty for perpetrating that myth! I remember 10 years ago having to go out and find some tyres for a photo shoot, because they wanted to see me dragging tyres.

I’mm very geeky about fitness stuff. One of the fun challenges with what we were trying to do in Antarctica was the fact that it involved completely conflicting forms of fitness. In some ways, it was an ultra ultramarathon. We did 70 marathons back-to-back. But in other ways, it was like a strongman contest. We were trying to pull this crazy amount of weight at the start, 200kg each, and doing five 5km in eight hours. It was a weird thing to train for. We did a lot of endurance training, but lots of strength training as well.

I think over the years one of the really important things about training for expeditions of any sort is giving yourself some kind of mental reference, particularly if you’re doing stuff with a team or even if it’s just one other person. Doing stuff together that’s really hard even if it’s not specifically relevant to your trip is a great idea. Tarka and I did a ridiculous race the summer before Antarctica, a vertical kilometre race in Chamonix. It was basically a running race up the side of the mountain. It took less than an hour. Compared to a three and a half month expedition, it was totally irrelevant but it was really hard. It was intimidating because I’mve never done a race like it before. It got us out of our comfort zone and it was a mutual reference point.

Alastair: Well, I hold you directly responsible for getting me to enjoy deadlifts. Until we started training together I would not have been seen dead in a gym!

Ben: I blame Mark Twight. He wrote this wonderful book, Extreme Alpinism. I’mm not even a mountaineer, but I love this book. It came out in the ’90s. It’s a handbook for his style of mountaineering, what he believed in, and what was important to him. Immediately I thought, “This is what I want to do in the polar world, I want to be a professional like this. I want to have the same level of attention to detail when it comes to training, and the equipment, and the mindset”. He had this monk-like focus… At the time when a lot of climbers would rock up in a camper van and get stoned or drunk the night before and then sort of stumble up the face, he was like an athlete. A lot of the records he set still stand now.

Alastair: And I hold Mark Twight directly responsible for his book Kiss or Kill that validated my theory of life that something’s only worth doing if it’s deeply and utterly miserable.

Ben: [laughing] Absolutely. I’mve got the book here. I love this phrase, “Training for Alpine climbing, if you sum it up in one phrase, is to make yourselves as indestructible as possible. The harder you are to kill, the longer you will last in the mountains.”

Alastair: Brilliant.

“Training for Alpine climbing, if you sum it up in one phrase, is to make yourselves as indestructible as possible. The harder you are to kill, the longer you will last in the mountains.”

Alastair: I would never have done any polar type activities at all if it was just all down to me – beginning the whole process is too hard for me. Similarly I wouldn’t have rowed an ocean either if it was all down to me just because there are so many skills, and knowledge, and money and all these things that I’mm rubbish at involved and the whole thing just seems overwhelmingly daunting. So if someone was wanting to begin polar journeys, what would your advice be?

Ben: I think it’s pretty important for your first expedition to tag along with someone else, or with a team, or to try and get out there with someone who’s more experienced than you are.

That could mean joining a guided expedition doing a last degree. It could mean getting a team and people together. It could mean tagging on to someone’s expedition. Try to get an initial experience just to see if it’s actually what you hope it’s going to be, with minimum investment in terms of cash and risk and that sort of thing. There are lots of people that do guided trips now.

Alastair: What do you know now that you wish you’d known when you set out on all of this stuff?

Ben: Crikey. I don’t know.

Alastair: Maybe you’d have taken one more bag of food to Antarctica?

Ben: Yeah, I definitely would have taken a day’s more food to Antarctica. I might not have taken the giant satellite transmitter, that would have saved a few kilos, though I wanted it to be a pioneering journey technologically, and I love that we did things in that respect that had been impossible until now. In the grand scheme of things, I’mm not sure when looking back. Even though I’mve got this string of non-starter expeditions or equipment failures, I don’t really regret them. They were all part of the process, and part of the journey, and part of overcoming these challenges that makes it so satisfying.

Alastair: That’s a good place to be. My final question then is, and this will be a hard one for you to answer because I know you spend more money on a bicycle than this. But if I gave you £1000 to go on an adventure, what would you go and do?

Ben: I remember being very impressed years ago by a guy called Mike Cawthorne. I’mve never met him. I hope he reads this because I think it’s important for people to realise that they’ve sowed little seeds that go on and inspire people. He wrote a book called Hell of a Journey. He climbed all of Scotland’s 1000-metre peaks in the middle of winter. It sounded incredibly hard. I remember him going a long period, I think it was 10 or 11 days without seeing another human being and that’s on mainland Britain. One of the things I feel sad about is that I might have perpetrated this idea that you need to go somewhere really exotic and faraway to have a meaningful experience or a challenging adventure. That is not the case at all.

Mike’s Scottish epic is such a tough journey that I’mm not sure I’mve got the winter climbing skills and experience to actually undertake it, but it would cost very little. One day, if I’mm man enough, that might be a trip that I would have a go at. No huge PR campaign or London launch party, I’md just go and try to link up all these hills in Scotland in winter. It would be an extraordinary journey.

Alastair: Brilliant. Thanks, Ben.

Follow Ben on Twitter and Instagram at @polarben

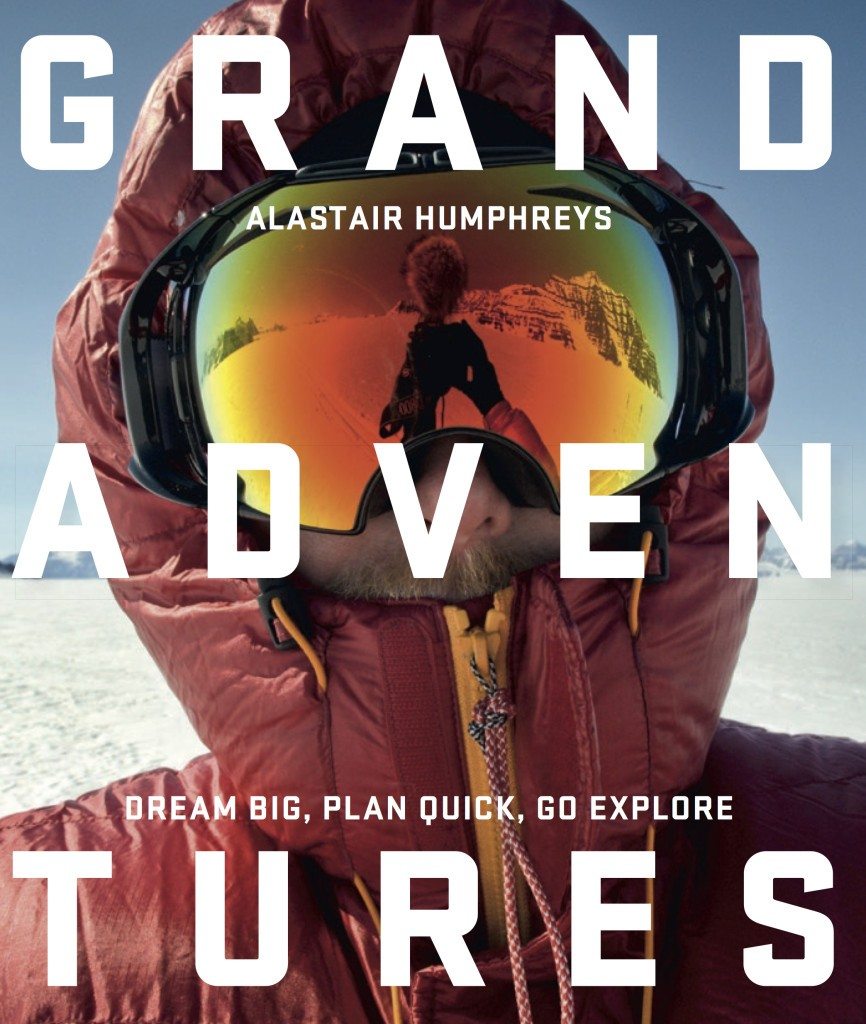

My new book, Grand Adventures, is out now.

It’s designed to help you dream big, plan quick, then go explore.

The book contains interviews and expertise from around 100 adventurers, plus masses of great photos to get you excited.I would be extremely grateful if you bought a copy here today!

I would also be really thankful if you could share this link on social media with all your friends – http://goo.gl/rIyPHA. It honestly would help me far more than you realise.

Thank you so much!

Grand Adventures from Alastair Humphreys on Vimeo.

Comments