Cas and Jonesy are a duo of Australian adventurers. They’ve paddled across the Tasman Sea, done an enormous South Pole expedition, and even released a jigsaw of themselves! I caught up with Cas for a chat on Skype for the Grand Adventures project.

Alastair: My first question, which is slightly out of self-interest is, can you give a little comparison of a polar expedition versus rowing an ocean?

Cas: What are your views on it?

Alastair: You’d be a good politician! I’mve rowed the Atlantic, and I’mve been on an expedition in Greenland, though only for a few weeks. And then later the same year I walked across a bit of the Empty Quarter desert later that year. And what struck me about those three trips was how similar they all were. They were all in an environment that was very bleak and empty, and would kill you. And your entire survival depended on the few bits of kit you had and the teammates you had. And although they seemed incredibly different, they were virtually identical experiences.

Cas: Interesting. I get really badly sea sickness. So, that’s one thing about Antarctica: it didn’t move, which was good! But I thought the Antarctica trip was harder in that there’s something about the cold and the wind that you just cannot escape. The ocean – regardless if you’re a kilometre off the coast or 500 kilometres off the coast – is beautiful. The birds are out, your shirt’s off, you’re getting some sun. There’s fish in the water. It’s really, really pleasant. Whereas I found in Antarctica, you just didn’t get the same time off and the same respite. It was just constant and incessant, whereas at sea, I felt that you could, on a nice day, relax.

Alastair: That’s interesting you say that. The incessant-ness of expeditions is what really grinds you down. For me, whereas the desert was baking horribly hot in the day, at night it was cool and you could sleep. Or, on the ice (which was nowhere near as cold as yours), I’md get into the sleeping bag at night and it would be warm and still and I’md get a whole night’s rest rather than the sea where you get woken up to row every two hours and it was always bloody moving and wet and salty. Salt water in everything and jeez, it just pissed me off! We were doing two hours on and two hours off, 24 hours a day, which I think, added to the incessant nature.

Anyway… Back in the day when you had a proper job, you were an accountant: a decent graduate job, good income. You were climbing at the weekends, having occasional climbing trips away. Why wasn’t that enough?

Cas: I looked at the managers five years ahead of me, then the partners that were 10 or 15 years older than me, and I looked at the lives that they are living and I looked at what was really important to me. And I just couldn’t see myself living like they were living. And conformity has always freaked me out a little bit. And so this was a way of identifying who I was and what I was capable of doing and just seeing a bit of the world.

Conformity has always freaked me out a little bit.

Alastair: I think that thing you said about looking at people 5, 10, 15 years ahead of you and imagining that becoming you is a really important thing to do. To look ahead, see what you’ll become if you carry on as you are and then work out if you want that or no. And if you don’t want that . . .

Cas: Yes, you are who you hang around with.

Alastair: And therefore, at some point, you have to step off the conveyor belt.

Cas: Yeah, you do. And I think the younger you are, the easier it is to do that. Even at the time, it was the hardest decision I’md ever had to make in my life. But now, with a young family, if I had to do it now, I don’t know if I would have had that will.

Alastair: Back then, you were young, free, very single. So why was it a difficult decision?

Cas: I come from a Greek family. And my Mum and Dad had invested so much in my education and had it all planned out for me, really. You go to school, you go to Uni, get a good job… To turn my back on that was almost like a bit of a slap in the face of Mum and Dad. Not living up to their expectations, no one understood why I was doing it. That’s what made it so difficult.

For a big adventure, there are four phases.

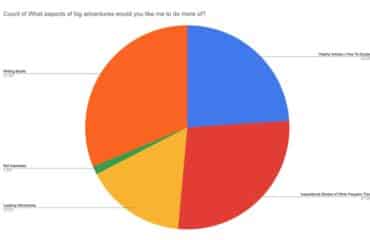

Alastair: I reckon that for a big adventure, there are four phases. I want you to rank these in order of difficulty.

- Quitting whatever you were going to do and committing to getting on with it.

- Getting the cash together to make it happen.

- All the actual preparation.

- The trip itself.

Cas: Definitely, the trip is the easiest.

Alastair: Yes!

Cas: By far, the easiest. The second easiest would be the preparation because you’re kind of in trip mode for that. The hardest would be that first step. I think the chronological order is the right order in that committing to, really properly committing to it up front, is the hardest. Financially, I think a lot of people struggle with the financial side of things: we definitely have in the past. I kind of revel in it though. I enjoy that challenge whereas a lot of people don’t. I really enjoy going out after it. But that real 100% commitment is a tough thing to get to.

Alastair: It’s a shame that that’s the first thing isn’t it? People see a vision of this brilliant adventure they want to have but they have to do the hardest bit first. It’s like the most beautiful rock climb in the world, up to a lovely sun-lit summit. But right at the beginning, before you even get off the ground, is a ridiculous overhanging crux move.

Cas: That’s exactly right.

Alastair: For people like you and me, people who’ve had education and live in a wealthy country, we’re not going to die of starvation. The decision is not a life or death decision. If you’d quit your job and said, “I’mm going to go do this,” but then sometime down the line, realised you’d done the wrong thing, you could have gone back and got another job. Trying to make folk realise that this is not a life or death decision is quite important.

Cas: I think there’s a lot of truth in that.

“Aren’t you going to get eaten by sharks, aren’t you going to fall down down a crevasse?”

Alastair: So now someone has done the difficult thing, they’ve told their family they’re going to do it. They’ve quit their job. What are some practical things that needs to be done then, to get to the start line of an ocean or polar journey?

Cas: We put together a risk management document, on paper. For the Antarctic trip, it ended being about 100 pages. It laid out what systems we needed, what gear we needed, what were the risks, how we could address the risks. It proved such a valuable document in engaging stakeholders. When you go to a meeting with a potential sponsor, they’ll be asking all the typical questions, “aren’t you going to get eaten by sharks, aren’t you going to fall down down a crevasse?”

And instead of spending the whole meeting talking about that stuff, you can literally pull out the document, give it to them and say, “Look, we’ve done some detailed research on all these, have a read through in your spare time. But today, we’re here to talk about X, whether it’s sponsorship or may whatever it might be.”

We found out it was a really good way in,

- A – getting our heads round the trip, going from a concept to something we could actually see

- B – it’s a great stakeholder tool because they don’t see you just as crazy adventurer, but more as a competent risk mitigator.

Alastair: I like that. Although we all do these adventures for fun, at some point, if you’re going to actually make something difficult happen, then you have to sit down and take it seriously and put in some serious work. Here you’re basically treating it like a proper work project in terms of professionalism. You’re now at a point where you’re a professional adventurer. You’re well respected, you’re well known. At what point did you start to think the passion of your first adventure might become your job?

Cas: When we got back from the Tasman Crossing in 2008, this is how green we were: we didn’t even know a world of corporate speaking existed. And so, when we got back, we started getting a few emails from some companies saying, “Can you come and speak to our staff?” We were able to develop something off the back of that. But initially it was 100% about doing the trip and life after it didn’t even really exist. It was just about doing the trip. And we were going to deal with life after that. We didn’t even have clothes organised when we arrived in New Zealand. We didn’t have shoes! Life after the trip just didn’t enter our heads.

Alastair: So when you began to plan the row, you had no idea what was going to happen in life after the trip?

Cas: No idea. In fact, we used up all our money.

Alastair: I think for a lot of people, these two things are pretty terrifying concepts. Using up all your money and the uncertainty. I’mm sure your friends and family must have worried and thought you were being silly and irresponsible, didn’t they?

Cas: Yeah, definitely. Definitely. It was incredibly terrifying.

Alastair: What advice do you have then for somebody who is dreaming of adventure but finds it slightly too reckless to actually do?

Cas: I guess you could make sure your career’s in a position so that you can come back to your job; having that door open. I guess that would be quite a comforting thought.

Alastair: Yeah, that’s a good one. Now, you’re career is doing so well: you’re the only professional adventurer I know who sell jigsaws of themselves. [laughing]

Cas: How embarrassing! [laughing]

Alastair: That means you’ve made it to the big time!

Cas: That’s embarrassing.

Alastair: A serious point though in terms of trying to make it your job is that in order to earn enough money to live it involves a lot of work, a lot of entrepreneurship, but also some things that are a little bit embarrassing…

Cas: Yep!

Alastair: I find it uncomfortable that my job is basically showing off about myself on the internet.

Cas: Me too!

Alastair: But I guess that’s the compromise you have to make to do something you love?

Cas: There’s a constant conflict between doing what you love and the commercial side of adventure, if you know what I mean. The idea of being commercial about it and making it a business almost sounds dirty. Overcoming that and combining the two can feel a bit complicated sometimes.

There’s a constant conflict between doing what you love and the commercial side of adventure.

Alastair: People completely accept that adventurers do talks to make money. That’s what they’ve done for a 100 years. Scott and Shackleton did hundreds of talks to get cash. So, I think people accept that, and it doesn’t seem dirty and a sellout. But then, I started doing corporate micro-adventures, and I’mm being very cautious about whether that’s crossing over into exploiting adventure. I’mve been cautious to not really advertise my corporate micro-adventures. And consequently, I had very few bookings. [You can find out more here, if you’re interested!]

Anyway… You and Jonesy went off and did this trip together because you are friends and your book is brilliant about documenting the pros and cons of trying to get the trip off the ground with a friend. Can you just give me a couple of the pros and cons of doing that big trip with your mate versus doing it on your own?

Cas: I think when you come together for a common objective with a friend, you’ll always go that extra mile and do that little bit more for that person than you would have if it was a professional relationship. You know, if it was just the objective that was holding you together, versus when there’s love there, you’re going to go further. And you are not going to want to let that person down.

In terms of doing trips on your own, some people operate really well on their own, prefer their own company, and achieve more on their own. But when I’mm down on a trip I need that physical presence of someone else to pick me back up. I love sharing the good moments with people, and being able to interact with someone when those amazing points happen on an expedition. I like being with my friends.

Alastair: I interviewed a guy – Nic – who decided to see how far he could cycle with his mate for £1000. They set off from the UK and he made it to Tokyo. But his mate got as far as Russia and then quit. But Nic said that he really valued his mate having been there just to get him to the start line. When I read your book, what struck me was that, the thing that would have stopped your row happening was Jonesy. You on your own would have done it. You would have made it happen. He was less committed to it, off partying, and it could all have faltered because of him, I would say. So there’s a risk of two people not being equally invested in a project and therefore it might not happen. Is that fair?

Cas: It is fair. Some advice I got back when I was having a big difficult patch with Jonesy, a friend said to me, “Look, even if you are responsible for 80% of the project, 80% is not going to get you to the start line.” And that’s with me operating 24 hours a day. So if Jonesy only did 20% that was enough. But then we’re on the trip itself, that’s really where Jonesy’s strong point is. He more than made up for everything out on the trip itself.

Alastair: I think that’s a really good thing to remember, isn’t it? There’s a lot of personality types required in making a trip like this happen. You doing the stuff to get to the start line and then his personality helping you both get to the finish line.

Cas: Yeah.

Alastair: I really loved your Crossing the Ditch book. It’s fantastic. It’s really, really good. Trying to write about crossing an ocean has got a hard thing and most of the books on it are a bit boring, because it’s all a bit repetitive.

Cas: Oh, that’s good to hear. Since I was a kid, I loved reading adventure books. But always, after you get to the end, you kind of think, “What were they really thinking? And what was really going through their head?” There’s always this filter that they all throw over the adventure. They wrote in a way they wanted to be perceived and wanted the situation to be perceived. I wanted to cut through that for good and for the bad and the ugly.

Alastair: Yeah, you did really a good job with it. Have you read any of Andy Kirkpatrick’s books? He’s very good at being honest as well.

Cas: Yeah, brutally honest.

Alastair: What are you working on these days?

Cas: Last May, Jonesy and I filmed a TV pilot in the US. We kind of cocked it up. We did a really bad job. Doing an adventure with a film crew very much changed the dynamics of how we do stuff. It felt contrived and I don’t feel too confident in it, actually. But it was a cool experience and we just have to wait and see what happens.

Alastair: Do you think you’re always going to struggle with a TV crew, the sense of integrity, having filmed stuff yourself?

Cas: Yeah, I do. Because when you go out there on an adventure, you’re there to have an adventure primarily and the filming happens as a secondary objective. Whereas when you’re there with a film crew, your primary objective is to film and secondary to that is the adventure. I feel that impacts on the authenticity of what you’re filming unless you’re a very good actor.

Alastair: Yeah. When I made my desert film with Leon, that was the first thing I’mve ever filmed properly. Actually, our primary aim of that trip was to make a film. What was so difficult was, whenever anything interesting happened, you then need to reenact it for the film . . .

Cas: Yup.

Alastair: . . . and that’s too late. Or, if we ever decided we need to just have a big discussion about something, we’d set up the cameras. And then, it was just really awkward, it’s like setting up cameras in your bedroom, just weird [I imagine]. So we definitely struggled with trying to make a film with just two people was quite hard.

Cas: Did you enjoy it much?

Alastair: I loved the filming process. I really did. I felt that it changed the trip in some ways. You know, those days when there’s not much happening and you’re just trundling along, I was freaking out because nothing was happening and I needed to make a film. But on the positive side, it really made me more observant.

Cas: Yup, sure.

Alastair: Did you originally set out on your trips because you wanted to film them or was the filming tagged on to the desire to do the adventure?

Cas: We didn’t have a pre-sale with either of them. We really struggled with that part.

Alastair: Do you think anyone can sell an adventure film up front?

Cas: I think it’s a really hard slog, but I think here in Australia, at least it’s easier to get a network sale. What do you find over there?

Alastair: I think it’s virtually impossible really, unless you’re famous. Which means that if you’re wanting to go and film it well, that’s a hell of a gamble of effort. You’re spending a huge amount of effort for something that might come to nothing. You have to really want to do it. Which one of you two cared about the film?

Cas: I wrote both the books and Jonesy co-produced the documentary. So, he was the one more driving the post-expedition stuff. The actual filming on the trips, we both enjoy that. But when you’re on a proper trip, it really does compromise the trip itself, so you can only really give it X amount of time per day or per week. Otherwise, it can just get out of hand.

Alastair: That was always a challenge when I was training with Ben for the South Pole. We definitely had differing opinions on the film side of life. You need to both have similar goals, I think. Anyway, are the two of you itching for another big trip?

Cas: Yeah, I just don’t know how to balance it at the moment. I would actually love to do a trip up in the Arctic. I’mm just really fascinated by the North. We did some training with Richard Weber up in Northern Canada in February this year. But yes, I’mm not sure if the next one we’ll be together or not. I’mm trying to balance the ambition of wanting to do something like that with family and spending time at home and I don’t know if there’s an answer to it.

Alastair: I’mm not sure there’s an easy answer! I guess you have to be selfish and do the trip you want to do, or be a good family man and feel the regret of missed opportunities. That’s my cheerful answer. That’s why I’mm a motivational speaker. [laughing]

My final question for you, is what adventure would you do for £1000?

Cas: Now I’mm getting into technicalities. Is that £1000 cash that I can use after pulling a few strings, getting a few people involved…?

Alastair: Whatever you feel like. It’s a loose question!

Cas: Yeah. I think, I would sail out to Balls Pyramid West Face and climb it: it’s 680 meters high, but 500 kilometers off the east coast of Australia.

Alastair: Wow, that’s amazing.

Buy Cas and Jonesy’s books and films and jigsaws here.

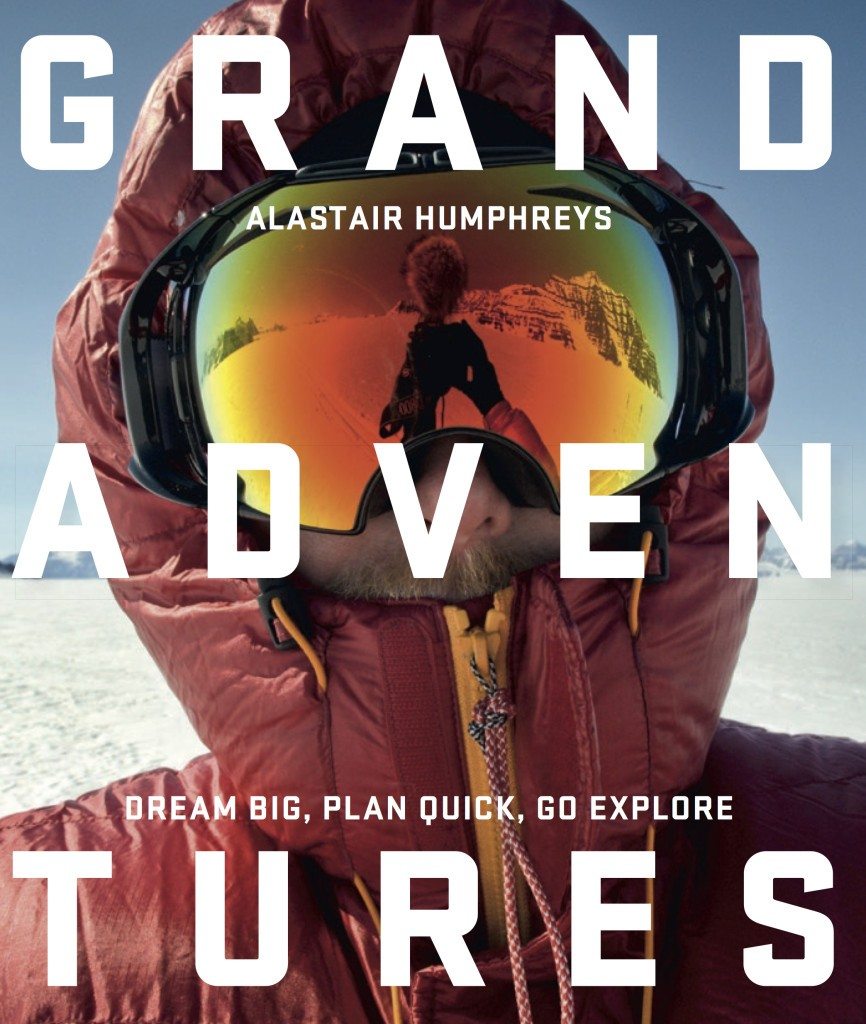

My new book, Grand Adventures, is out now.

It’s designed to help you dream big, plan quick, then go explore.

The book contains interviews and expertise from around 100 adventurers, plus masses of great photos to get you excited.I would be extremely grateful if you bought a copy here today!

I would also be really thankful if you could share this link on social media with all your friends – http://goo.gl/rIyPHA. It honestly would help me far more than you realise.

Thank you so much!

Grand Adventures from Alastair Humphreys on Vimeo.

Comments