Australian adventurer Tim Cope has cycled across Siberia and rowed the Yenisey. He has also travelled, by horse, for three years across Eurasia. I had a great chat with him for Grand Adventures.

Alastair: Can you give me a simple summary of your grand horse journey?

Tim: I set off on the trail of Genghis Khan by horse to retrace and discover the spirit of the nomadic people of Eurasia.

Alastair: It was an amazing journey. The beauty of the Altai mountains, temperatures of minus 50 – which is epic – the Kazakh Desert, the heat, the Carpathian forest… it’s just a wonderful journey. What was most important to you at the start, that wilderness stuff or the Genghis Khan / nomad journey side of things?

Tim: I think at the start everything was tied in together. On one hand, it was the prospect and the endless possibilities of what might happen in this environment where there are no fences for 6,000 miles. You set off on the horse, and from day one to the finish, it’s unpredictable. It was an unscripted life that I was looking for and a sense of freedom. That was what I was really looking for. But at the same time I really wanted to understand who these nomadic people were. It just really beguiled me about how they lived in this environment with an attitude that kind of debunks the way we live in settled western society. The concepts of private property don’t exist. People adapt their lives to the animals rather than the other way around.

Both of them were key to my inspiration and the horse seemed to marry every thing together, because the horse gave me that insight into an ancient world, it allowed me to transcend the modern era, and it just gave my the freedom to move away from the roads and experience what these nomadic people have always known. The freedom of that environment. Does that make sense?

Alastair: Yeah, it does, it’s a wonderful story. I recently spoke to a girl called Hannah, who walked a thousand mile lap of Wales, her country, with a donkey. For her the donkey was the ultimate icebreaker. Was that a big difference between the horse trips vs. your bike trips, the icebreaking effect of conversation?

Tim: It even went beyond that, in the sense that every time I got on my horse I had two pack horses behind and my little dog, Tigon: it was like stepping into a folk tale each day. Arriving by bike was one thing, an icebreaker in the sense that people saw me as a great novelty, strange and out of this world. But arriving on horse was the most natural thing to them because the horse has been a part of their culture for many thousands of years. On one hand they saw me as a foreigner and an interest, but on the other hand they understood me and could sympathise with me in a way that wasn’t possible with any other mode of transport.

Much more than that I think, the horse enabled me to experience what it was like for people centuries ago. A horse, and the needs of the horse, haven’t changed since the beginning of time, so it enabled me to transcend the modern era. In places like Kazakhstan and Hungary the nomadic way of life has largely been eroded away. By arriving on a horse in a village, suddenly it brought to life a lot of that culture because what’s lacking in a lot of those places, is the horse itself.

When I arrived on a horse, people who had never ridden horses, or hadn’t lived the nomadic life at least, suddenly all of the things that their fathers and grandfathers had told them about horsemen and the horse life [came rushing back to them], traditions like, “You should never let a horseman pass your family home, you should always bring them in for three cups of tea, and if possible host them for three days.” The horse enabled me to re-experience a way of life that has slipped into the past.

Alastair: The idea of the horse journey came to you when you were cycling across Asia. Some horsemen appeared from nowhere. You realised that on a bike you’re always limited to the track or road. That was something that always frustrated me. You realised that the horse opened a world without boundaries: 6,000 miles without a fence. What were some of the other differences between a bike journey and a horse journey?

Tim: This might sound strange but something I hadn’t really anticipated before I set off is that on a horse I lost my independence. The journey completely revolved around the well-being of the animals. I could only ever camp where there was good grass and where there was water. I could only travel as far as it was healthy for the horses to travel.

Alastair: That’s a lovely antidote to the selfishness of the long distance explorer.

Tim: Yeah, it only sank in after I set off. It was very hard to find people I could trust, and I found that when I was alone with these animals I felt much more vulnerable than I ever would have been on a bike. That’s partly because I couldn’t just get back on and ride off. I had to wait two or three days if the horses needed rest or there were other issues I had to deal with. It made me much more dependent on the knowledge and the help of local people. In a way my life was in their hands. I experienced a sense of vulnerability that I had never experienced before. If you see a beautiful hill with a beautiful view, but you can’t just go there and camp there with a horse, because the horses need 20 to 30 litres of water each a day, and it needs to be a place with good grass and good shelter and all the rest of it. That was a challenge, and it hadn’t been something that I was really fully expecting.

Alastair: That’s interesting.

Tim: The flip side of that, is that the horses, as a result, completely tied me to the environment. From Mongolia to the Danube in Hungary I can still recount in my mind pretty much every patch of grass along the way. You start to learn to look at the world through the eyes of a horse. The world looks very different from horseback than other modes of transport. You start to look out for threats and problems. Cities appear particularly unfriendly when you’re on horseback, and they actually appear extremely dangerous. One of the great things was that horses can literally cross raging rivers, you can go through snow, up mountains, you can go on tracks as well, but they are incredibly versatile and you can go a long way. The other thing, of course, compared to bicycle journeys is that it’s a lot, lot slower.

Alastair: What was an average day’s distance on a horse?

Tim: Between 20 and 40 kilometres. And you also needed to build in lots and lots of rest days for the horses to keep up their eating of grass and keep their weight up.

Alastair: I think I’md like being forced to slow down on a journey because my tendency, my instinct is to always bash out a few more miles. I always appreciate it more when I force myself to slow down.

Tim: Yeah, and you’re really forced to slow down on horses. My only regret for the whole journey is that I went through Mongolia pretty fast. I attacked Mongolia a little bit from my western mind set. I had a plan, I wanted to make it to Hungary in 18 months, and I rode reasonably quickly. I did all of Mongolia in about three or four months, and I was really slim, and skin and bone at the end, and exhausted. I had a wonderful experience, but had I known that the journey would only take three and a half years…

Alastair: That’s quite an underestimation!

Tim: Yeah, had I known that at the start, I would have spent six months in Mongolia. I think one thing that gets forgotten is that the horse is not really a mode of transport, it actually becomes your companion. The relationship with the horse and your animals becomes the essence of the journey. It’s like you’re all in it together, and you are travelling and you’re moving, and you’ve got a goal but ultimately the goal is to find enough food and shelter and water to keep everyone healthy and happy. The route that I took evolved day to day based on how I could manage that.

Alastair: I want to ask you a couple of questions about life after a trip like this. You say it involved many years of dreaming before you began. Then there was 18 months of planning. It was a three and a half year journey. Overall it was a pretty big commitment to a dream and a goal and your lovely phrase about looking to live an unscripted life. How have you coped with life after this big journey?

Tim: Well, it’s been I think it’s always more difficult to adjust to life after a trip than it is to adjust to life on the road. Australia was a bit of a cultural shock when I arrived home. I left my horses behind, I didn’t have my dog Tigon and people had no idea what I’md been through or what I had experienced. I spent two years making the film and then four years writing the book, so in total, including the journey and the preparation, you’re talking about a ten year project. It feels as if it’s still the one journey, it’s just that every stage of it is different. There’s the preparation stage, the journey stage, and then the journey of reflection and digestion, and sharing with other people.

I think honestly that sharing the experiences through writing and film has been the way that I’mve been able to reconcile the differences between living in Australia and living on the Steppe and the fact that it’s too easy to dismiss these very different cultures and parts of the world as being irrelevant and primitive and as being a kind of a society that we’ve moved on from.

Alastair: What did you know at the end that you wished you’d known at the start?

Tim: Mostly, I wish I had known that the journey might take as long as three and a half years, because I would have travelled at a slower pace through Mongolia, instead of trying to stick to my plan. Perhaps more importantly though, had I known that my father would pass away during my journey, I would have done more to encourage him to come over to the steppe and join me for a section of the journey. He had retired during my trip, and theoretically could have joined. Unfortunately dad, an outdoor educator and believer in experiential education, was killed in a car accident when I was in Ukraine less than 1500 kilometres from the finish. That became the biggest challenge for me, and I still think about how I would have loved to share some of my experiences with him.

Alastair: I’mm really sorry to hear that. He must have been very proud of you…

I love looking at the northern-flowing Russian rivers on my maps and scheming ideas so I love your Yenisey paddle. How did you cope for 4 months on a 5 metre boat? I was on an 8 metre boat rowing the Atlantic for 45 days and that felt hard!

Tim: Physically the rowboat journey was not as difficult as riding a bike, or travelling with horses (the easiest day on the horses was still probably harder than the hardest days of any other journey I had experienced), although it was inconvenient that we rowed 24 hours a day on 2 hour shifts, so sleep was always in short supply! It was a beautiful experience to float through the heart of Siberia watching the landscape and people change as we neared the Arctic Coast. The boat itself was a story – we found the rotted out hull of a boat on the shores of lake Baikal and were told that the owner had been knocked off by the mafia! We took the boat away and spent three weeks building a cabin on the outskirts of the city of Irkutsk. We then spent 4 months or so rowing our way north, surviving on fish mostly, navigating some rapids and – more importantly – the large barges that would appear from the fog.

The hardest thing about the rowboat journey was simply surviving with four of us on such a small boat. When the coffee and chocolate ran low near the end tensions built, but there was nowhere to escape to for personal space. I found it ironic that here we were, in the middle of Siberia, this land of endless horizons of tundra and forests, yet we were living life in what felt like a cramped glass bottle! To me, the way to cope was always to focus on the rich texture of the land, the moods of the weather, and the fascinating people. That seemed to calm me, and allow me to ignore some of the cramped conditions, and lack of sleep and food.

Alastair: What is the coast like at the ‘end’ of that river? What sort of people live there?

Tim: By the time we neared the end, the river was about 60 kilometres wide and the current was meaningless. When the wind blew from the north we simply had to point the bow into the swell and hope we could maintain our direction, and often got pushed back upstream. The land at the river’s edges sprawled out in a sea of tundra with its brown, weather beaten hues, and was dusted with snow come the finish. We ended our journey in the Yenisey gulf on a small island where a couple of families of reindeer herders known as ‘nenets’ live. They took us to the beach where scattered human bones could be seen protuding from the sand – the remains of the many hundreds who had perished here when Stalin deported ethnic Germans from the Volga river to Siberia during WW2. The Nenets peoples are one of many Arctic peoples who live right across the northern realms from Norway to the Bering strait and beyond.

Alastair: Now this is your “career” does that impact on the simplicity of doing a journey just for the love of it?

Tim: This is a difficult question and the answer is both yes and no. I’mve always followed my curiosity and passions when it comes to journeys, and since a child have loved writing, and later film, so it has felt like a natural marriage to combine all these things. I still consider what I do a way of life, or rather an approach to life, but realised early on that it was all or nothing – one can’t do these kind of journeys books and films in spare time between jobs! So yes – it has become my way of life and my career all rolled into one.

It might be relevant to point out that for the horseback journey I was fascinated by the nomad cultures of Eurasia and realised the only way to really get into the fabric of their life in history was to ride a horse from Mongolia to Hungary. The freedom, the endless possibilities of what lay ahead also helped drive me to begin as well, but the challenge per se was simply an inevitable part of acting out my dream (not the focus). I haven’t changed in that way, I’mm always looking to where my heart is at, and what fascinates me most. And the reality is that all of my journeys have been based on a simple idea but proven very complex to carry out.

I think what is dangerous is thinking that one has a ‘formula’ for how to make a good journey, book, film work…. in reality every experience is unique, and formulae are often only obvious in retrospect. So, looking forward, I am searching for a simple idea that will allow me to pursue my passion in anthropology, wilderness, and culture. One of my ideas is to follow the gypsy trail from India to Europe.

I have always had a policy that I intend to stick to: never sign a book or film deal before a journey is complete. I think that by going out without these deals, the journey is simpler, there is less pressure, and there is much more authenticity, and the possibilities and prospects are left wide open!

Alastair: That’s really interesting – I chatted to Leon McCarron earlier in the year about his experiences of a pre-arranged film deal. My final question is if I gave you £1000 for an adventure, what would you go and do?

Tim: Well, for $2000 it’s hard to get far from Australia and do anything significant, so I would probably walk out my backdoor here in the Vic Alps with my dog Tigon and walk as far as I could through the Great Dividing Range. There is a network of trails here that begin in Victoria and end in Cape York. In the right season (winter) I would probably head inland to Australia’s interior. Australia, ironically, is a place that I haven’t explored in the same way as Eurasia.

Alastair: Thank you very much.

Follow Tim online here. You can buy his book and film too.

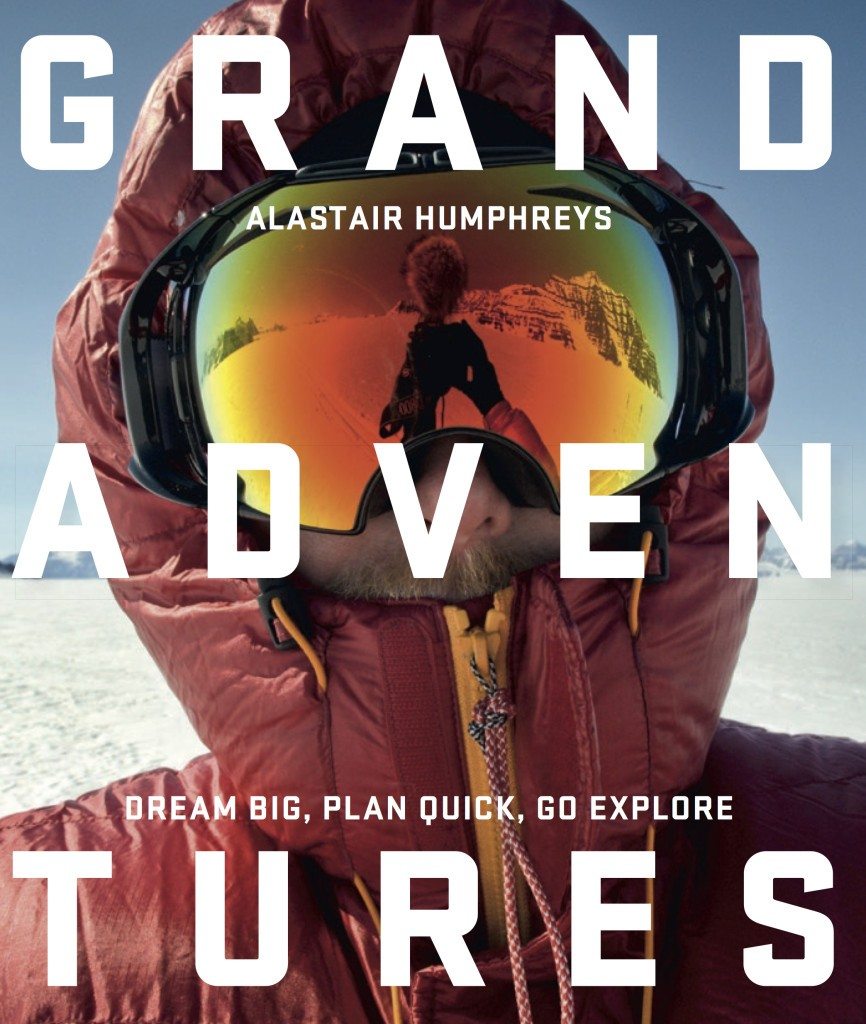

My new book, Grand Adventures, is out now.

It’s designed to help you dream big, plan quick, then go explore.

The book contains interviews and expertise from around 100 adventurers, plus masses of great photos to get you excited.I would be extremely grateful if you bought a copy here today!

I would also be really thankful if you could share this link on social media with all your friends – http://goo.gl/rIyPHA. It honestly would help me far more than you realise.

Thank you so much!

Grand Adventures from Alastair Humphreys on Vimeo.

Tim is a legend. I read his book a while ago. A fantastic, awe-inspring book that took me to places I have never been to before on so many levels.